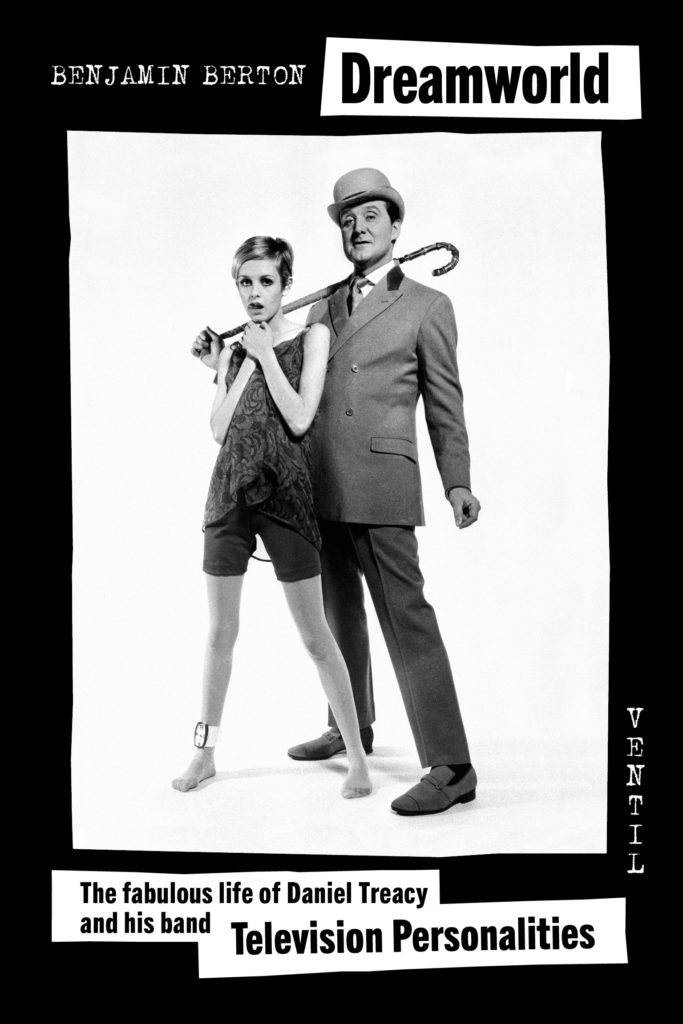

We don’t have to tell chickfactor readers who the Television Personalities are. We are thrilled to share an excerpt from Dreamworld: The fabulous life of Dan Treacy and his band The Television Personalities written by the French novelist Benjamin Berton. It will be published by Ventil Verlag on July 29 and distributed in the U.S. via Forced Exposure. We chose the chapter titled Alison Wonderland because it’s about love and photography along with great pop music and London (a few of our favorite things) and of course the TVPs!

chickfactor: Why did you want to write this book?

Benjamin: I’d discovered the band at the beginning of the nineties (I was born in 1974) as I was a huge fan of British pop music from punk to postpunk. It was a shock for me to discover such an intelligent and melodic band full of cultural references from movies, paintings and books, both sentimental and political, intimate and funny. It was like discovering some band as big and important as the Smiths except almost nobody seemed to know about them. At the time, I started writing books and music reviews for one of the first French indie rock webzines and I made the promise to write something consistent about the TVPs one day. I had written something like 10 novels then, got a few prizes but had always in mind the plan to write about a band. When I discussed doing something for Le Boulon editor round 2015, I started to tell Xavier at a lunch meeting about the dozen wonderful anecdotes I had about Bob Marley, Jimmy Page, David Hasselhoff and Daniel Treacy. We started at 11.00 a.m. and we parted 3 hours later. I realized it was time to write all this down and try to tell Daniel’s story from the beginning to where we were today, so somewhere near the end. And there was already at least 30 books about Morrissey and The Smiths, so why add another? CF

EXCERPT

Alison Wonderland

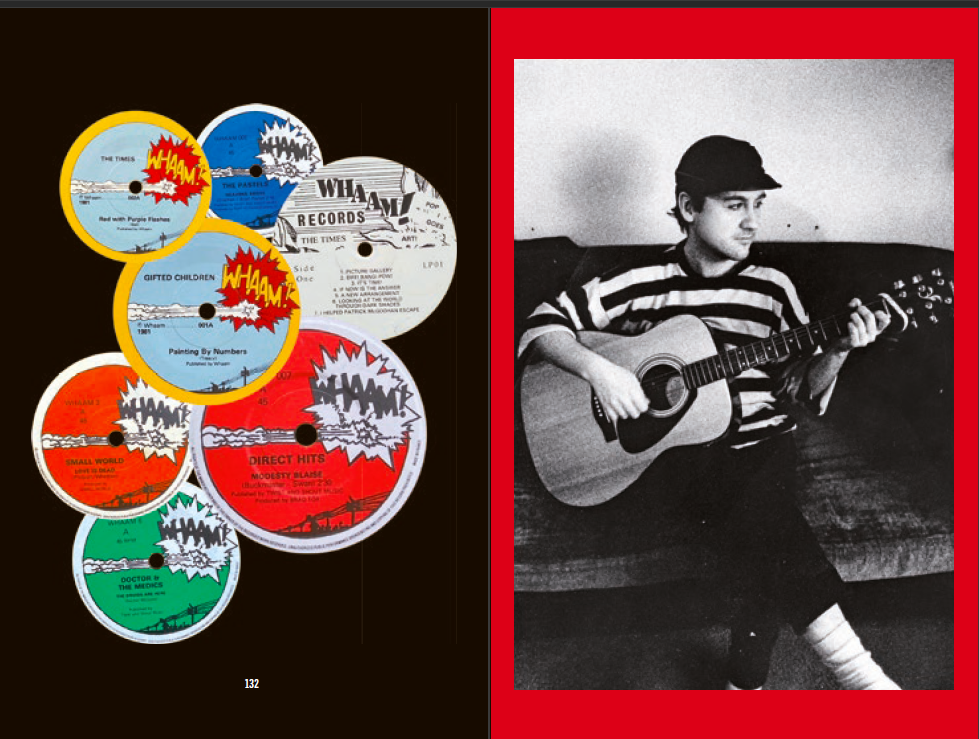

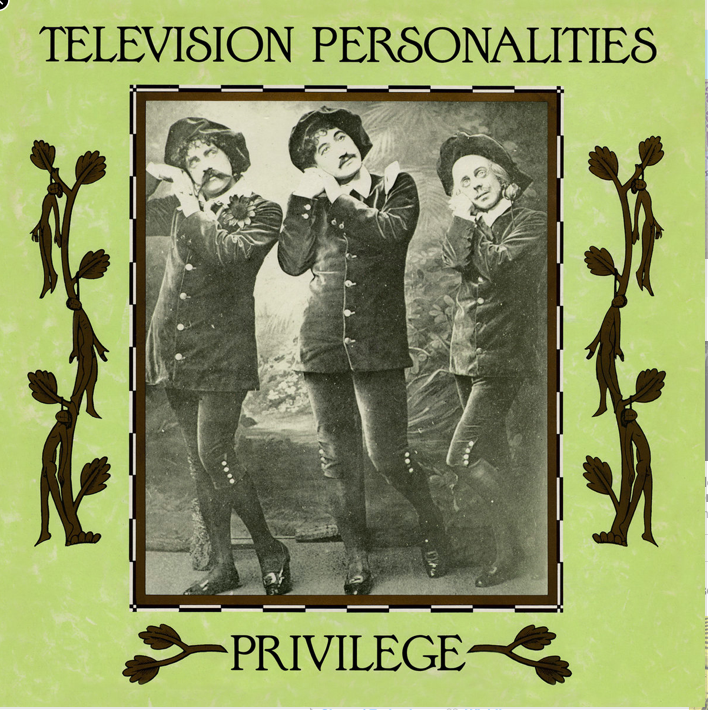

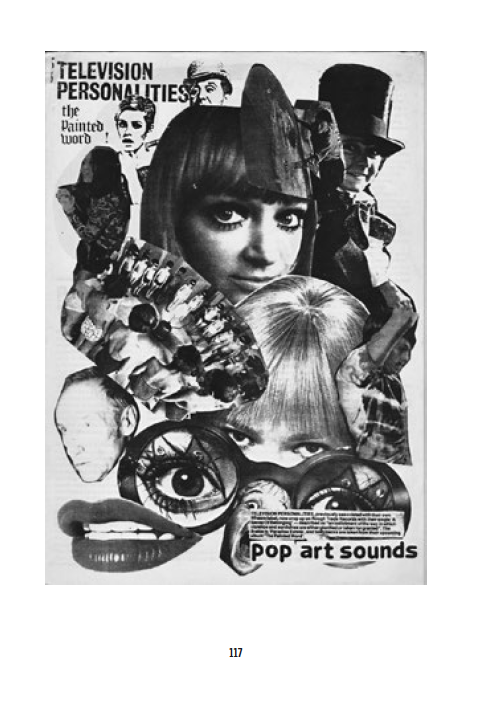

Six years after the issue of The Painted Word, the Television Personalities return to the 33rpm format with the album Privilege, released this time on the Fire Records label. The company had been set up five years before by Clive Solomon, a former acquaintance of Daniel and the Television Personalities. At the beginning, Solomon and the Television Personalities’ lead singer hung around the same London venues which heralded the psychedelic renewal. Moreover, he had organised gigs inspired by the 60’s even before McGee and others had thought of it, in a new club destined to become famous, the Groovy Cellar. At the time, Clive Solomon wasn’t directly a member of the gang, but hung around wherever they were. His favourite band, among all those who trawled the scene, was … the Television Personalities, who he had seen a good hundred times on stage and for whom he had tremendous respect. It was thanks to them that he had talked to McGee for the first time, and certainly also thanks to them that he had decided to pursue his career. Producer and occasional musician, Clive Solomon’s name figures, at the time of Whaam!, on Sha La La, the one and only single by the brilliant Jed Dmochowski, as executive producer. Whether that means he invested a few quid in the business, or that he was present during the recording sessions, is a matter of debate.

Be that as it may, in 1989 Clive Solomon is still managing Fire Records from his bedroom and is delighted to produce the Television Personalities’ new album, initially promised to Dreamworld. At the time, Fire has not yet defined its strategy, nor emerged as one of the best-entrenched and interesting independent labels on the market. The model would be simple: produce young artistes, but also welcome older guys with a history, in order to try and take over their catalogue via meticulous re-releases and promotion of their new songs. The label establishes itself by crossing the path of gifted and challenging bands like The Blue Aeroplanes, The Farm, Spacemen 3, the main event of 1989, Pulp (the band before success knocked on its door) Eugenius, Mission of Burma, or even Evan Dando’s band, the Lemonheads. It’s a small world. Fire Records has a reputation for allowing its artistes great creative liberty and giving them long-term support. Some are more critical as regards the personality of Clive Solomon. Luke Haines, for example, doesn’t spare him in the picture he paints in his book Bad Vibes. Solomon is described as a rather spineless guy, shy, bald and sallow, overplaying being nice to avoid conflicts. Haines, under contract to Fire with his band The Servants, quits in order to set up the successful band The Auteurs. If Treacy was to hold a grudge against Fire Records and Solomon, as he would against others later on, the release of Privilege and Fire Records’ support of the band in the following years with two intermediate EP’s and a further album, indicate clearly the attachment of Solomon and his team to the Television Personalities.

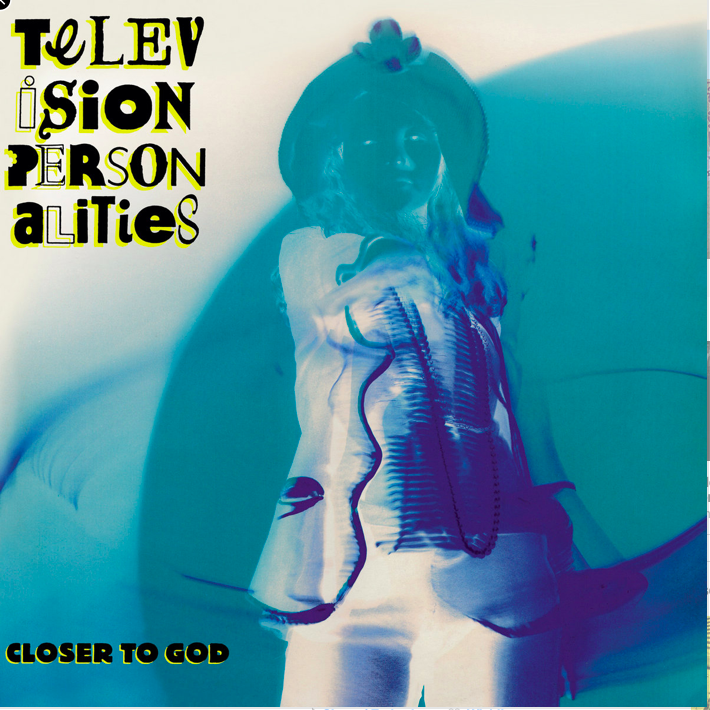

The label would moreover on several occasions re-release records by the Television Personalities, first in the early 90’s, then again in 2002 to 2003, and continue to accompany the group up until the issue in 2017 of an album containing rarities, demos and other unpublished works, prior to the release of Closer To God in 1992. It would be a lie to say that the label was well thought of by those closest to the band, but everyone agrees that Fire put a lot of energy into making the most out of the band’s reunified catalogue. Of the two albums released at the time on Fire Records, Privilege and Closer To God, it’s difficult say which is the better. The band’s fans usually place them a notch below their first album, which just goes to show the level of excellence achieved. The songs on the Privilege album, produced by Phil Vinall, one of the best British producers, were carved out and even recorded by the band in the course of three or four years of concerts. These are mostly remarkable songs, some even outstanding, which amply demonstrate the excellent health and the unimpaired genius of their composer. Phil Vinall replaces the insufficiently embellished parts, lightens the band’s sound and gives it a clearly pop colouration never attained up to this point. Apart from the weird My Hedonistic Tendencies, a synthpop track which jars and has aged a little, the album is still as pleasant to listen to, after almost thirty years. Daniel Treacy offers one or two compositions which belong to his former psychedelic and arty inspiration, of which the record’s signature song Salvador Dali’s Garden Party, is the best illustration. But most of the record comprises songs with more personal lyrics, where the inherent sadness is offset by the inventiveness of the tunes and the agility of the guitars. Such is the case of songs like Paradise Is For The Blessed, the sublime opening song, or of the sumptuous A Good And Faithful Servant which follows. The texts are redolent of the singer’s existential doubts, of the depression and solitude waiting in the wings, of the disenchantment (the terrible All My Dreams Are Dead) and of the fear of abandonment. The social and political aspects are always present (on Privilege or Conscience Tells Me No), but generally put aside in favour of sad songs which are among the most accomplished in all the band’s discography. Vinall persuades Treacy to emphasize his voice more, which turns out clearly to be a winning card. Never has the vocalist sung so well as on this album, achieving first-rate performances within his register in pieces like The Engine Driver Song, or the very moving What If It’s Raining? The studio work is fluid. Daniel is relaxed and receptive to suggestions. He knows the pieces by heart and doesn’t mind having to go over them several times. He likes to work quickly, plug in, play without wasting time then move on to something else.

Vinall, who in later years, would be involved for several months with the emergence of Jarvis Cocker (Pulp) and Brian Molko (Placebo), is all admiration. He knows that several of these songs are gems, but he also knows that Daniel is aware of his limits and is not infused with the conquering spirit and aggressiveness which produce superstars.

“These are my songs”, he seems to be saying as he deposits them at the feet of the producer. “They’re for you. I’d rather you didn’t return them to me”.

The mixture of rockabilly (Sometimes I Think You Know Me Better Than Myself), of wild or psychedelic pop rock and of lo-fi, give Privilege extraordinary power and richness. A few stylistic waverings may weaken the whole, but in no way lower the quality of the compositions. Privilege is released in February 1990 and has a cool reception, despite the issue in October 1989 of a sound single on the theme of Salvador Dali’s Garden Party. Fire Records does a low-key promotion of the album, accompanied by a British tour of five or six dates as openers for The House Of Love, which achieves little for the band in terms of notoriety. The House Of Love at the time is a band which has a certain success with the re-release of its first single Shine On and the release of their second album. However, the band is in disarray, having barely got over the sensational departure of Terry Bickers and saddled with Guy Chadwick, a leader sinking into a malignant megalomania weaned on alcohol and narcotics. It’s easy to imagine the benefits derived from being yoked together with the Television Personalities.

1990 continues with an endless German tour, but the sales fail to take off, despite an album of the soundest quality. Fire Records and the Television Personalities are not disheartened and release two new singles in the second half of 1991 and the double album Closer To God in 1992. Between these releases, Daniel Treacy, in need of money, signs with the Overground Records label for a series of re-releases of the band’s early singles. John Esplen, the founder of the label, owes his vocation to Daniel Treacy since it was during a conversation at the end of the 80’s that he had seemingly encouraged him to work on re-releasing oldies and afterwards offered him the possibility of reworking his band’s singles. Things would only come into being a few years later. I Know Where Syd Barrett Lives, then Three Wishes are thus revived, just like Smashing Time, Where’s Bill Grundy Now? and Favourite Films. The singles are simply accompanied by new jackets, created most of the time by Alison Withers, Daniel Treacy’s new girlfriend.

This frenzy of releases, for a band which is not necessarily often in the public eye, gives a strange impression to observers and blurs the communication connected with the new songs. Difficult to know, if you’re not watching closely, which songs are re-releases and which ones are new, particularly as the band now mixes enthusiastic up-beat songs with almost acoustic numbers where Daniel plays solo in a totally different register. Where does such a band fit in? What are they trying to say? If, at this time, the band still had any hope of achieving recognition other than esteem and acclaim, it disappears into an often brilliant, but for most people, unfathomable mist. The re-releases of the first albums on the Fire label add to the over-production which, while making the band’s music available once again, inspires the feeling that the Television Personalities have, in spite of themselves, become a nostalgic band of the past, bogged down in its own legend. Adding to that the live recording of a concert during the 1984 German tour, released apparently without authorisation from the band, it’s the last straw. It’s a false impression, since Daniel has never been so productive. Songs pour out like water from a tap.

When Closer To God arrives, Fire Records’ usual strategy, which consists in rekindling interest in the band via revivals of its old albums, doesn’t work. The signal is inaudible, as if jammed, and doesn’t manage to provoke any response. The album which contains 19 tracks is nonetheless monumental and worthy of the greatest interest. It’s easy to consider it as the band’s last great album and a magnificent demonstration of their talent.

Phil Vinall, who is producer again, returns to the more rock sound, full of effects and echo of the band’s beginnings, which, in the midst of the shoegaze and grunge wave, gives certain songs a really powerful impact. Closer To God is harsher than Privilege, but never departs from the melodic ambition and quality of the lyrics. The studio work is more extensive than for the previous album, since not everything has been written in advance. The music is meticulous, crafted, and once again, open to experimentation.

But for all that, it’s not “where it’s at” or in tune with what’s “in” at this moment in time. Psychedelia has had its day and British pop is not in much better straits. Because of being ahead of their time, the Television Personalities are caught between two worlds and, for the first time in their career, almost anachronistic.

Stylistic coherence is not always maintained throughout the 19 tracks. Some songs are weaker than others, but without much impact on the density and power of the collection. Closer To God is a double album and a further occasion for Treacy to reveal the scope of his talents. The cover, designed by Alison Withers, is strange and relates to no known universe. It’s not clear whether it does anything for the album which gets off to a cracking start with You Don’t Know How Lucky you Are and Hard Luck Story Number 39. In these two songs, Daniel warns the listener (and himself) in prophetic tones, against changes in fortune, drugs and decadence.

“Would you like to see scars?

My brand-new needle-marks? he sings like a show-off

You’ve got a job, a house, a company car

But you’ve still got shit for brains”.

The first piece is particularly violent, mixing biographical lucidity and anger directed against the well-to-do. The song ends with “Open up your mind, it’s an open door”, and like an ultimate copout, bids farewell to the world of escapism and psychedelics. Like the previous one, the album is a sort of patchwork of songs composed in the course of Treacy’s wanderings and inspirations.

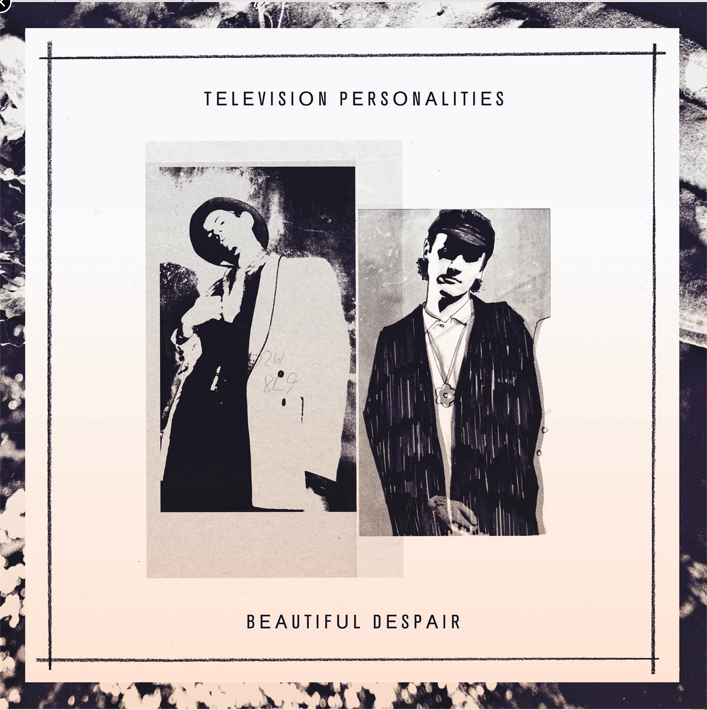

Between the releases of Privilege and Closer To God, Jowe Head and Treacy initially plan to produce a more intimate album which would only materialise twenty-five years later under the name of Beautiful Despair, a compilation of demonstration items and a few unpublished songs. Treacy literally forgets about the project, before re-injecting it by snippets into the monumental Closer To God. There’s an obvious impression that the band want to give it everything they’ve got. Everything is sweetness and light. And it shows: Treacy is in love. His bouts of anxiety, awesomely expressed in My Very First Nervous Breakdown or Very Dark Today, are contained and overridden by peals of laughter, great moments of self-mockery (the incredible Goodnight Mr Spaceman, the very T-Rex-like We Will Be Your Gurus) and above all some very fine love songs. The benevolent optimism of I Hope You Have A Nice Day is pleasant to listen to, but it’s the sentimental tracks which hit just the right tone that makes the album great. Even though he expresses a little clumsily his homesickness (Coming Home Soon) or his daft projects (Me And My Big Ideas) Daniel Treacy is no longer alone and drowns his sorrows in a one-to-one relationship which lights up his world. Few songs describe so well the ups and downs of love as This Heart’s Not Made Of Stone, and even less dwell on the loved one’s face with such attention and ability for amazement as You’re Younger Than You Know. This lofty, contemplative and luminous song is perhaps the greatest on the album. It’s a masterpiece of balance and delicacy in which the poetic images skillfully succeed each other, mixing naivety and sincerity as if it were a poem by John Keats.

“You’re looking younger now

Younger than the newest star

That shines up in the sky

Younger than the newest dream

Baby dreamt last night”.

It’s hard to tell if the narrator is describing the face of the girl he loves, or if he’s talking rather of the effect of love on his own features. However that may be, You’re Younger Than You Know leaves an impression of plenitude and fulfilment.

Closer To God ends with an autobiographical and existentialist eleven-minute-long title of the same name. Treacy comes back to his complicated relationship with the Catholic religion: his strict upbringing, a mixture of violence (at school and probably at home), of guilt and rejection. We know that his father was not a gentle soul and that life in the Treacy household was not always easy. We’ve already mentioned the nostalgic, but ambiguous relations that the singer had with his childhood. They are expressed here in a song carried by bass player Jowe Head, which is not entirely anti-religious, far from it, but transfers the issues of distress and depression into the realm of existentialism and the relationship with God. Maybe Treacy’s career can be interpreted as an attempt to evince a form of original sin, to defile himself and sink to the bottom in order, like the born again, to rise back to the surface. The song suggests as much, but you can’t be certain whether it’s not all an attempt at theatrics. Closer To God, by its length, its intensity and its ambition, seems to be the spiritual and equally disturbed counterpart of Back To Vietnam. Despite the scope of its dramatic impulse, this final song would rarely be singled out as one of the band’s best achievements.

With the release of two such important albums in less than three years and intermediate singles of this quality, at the end of 1992 the lukewarm reception makes things abundantly obvious: The Television Personalities are very unlikely to avoid their fate. British pop is at its lowest ebb. The American invasion is under way and despite favourable critics and reasonable sales, the band’s revival turns out to be a partial failure for Treacy and Fire Records. That doesn’t stop the trio from finally crossing the Atlantic for two successive American tours in 1992 and 1993, and going on tour in Japan the following year. But nobody is deceived by the band’s progress which has all the trappings of a breakthrough which only exists on paper.

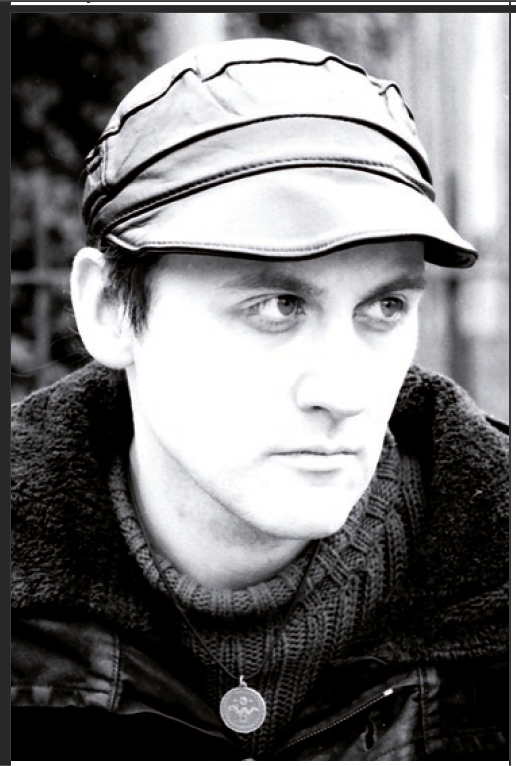

Things are starting to fall apart. Daniel Treacy manages to keep afloat thanks to the efforts of Alison Withers, one of the most important women in his life. Lover, best friend and colleague, Alison displays infinite comprehension. Daniel and Alison met up at the very end of the 80’s. The young woman figures on tambourine in a single released in 1987 by a friend of hers, Jerry Thackray, a.k.a. The Legend! She moves in the same circles as Treacy and meets the singer several times at the heights of his splendour. The two meet up one evening in November 1988 during a concert by the Spacemen 3. Daniel has come with Ed Ball. Alison is there with a girlfriend. Like a teenager, she sends her friend like a scout to ask Daniel if he would like to talk to her. Daniel stammers a yes and away you go.

At the time, Alison works in a library in Kensington, not far from Treacy’s parents’ home which is now perched over a Council depot in a block of flats wonderfully named “Sky Gardens”. Daniel had come back there to live after separating from Emilee and having spent several months of homelessness taking drugs and screwing up his head. Since then, he has sorted himself out a bit, surrounded by his family, even if he is still quite unstable. Alison also lives with her parents near Croxley Green, twenty miles or so from the centre of London.

Alison is young, knowledgeable, pretty too. She is free and lots of boys run after her. Daniel Treacy falls in love. And things continue, things go better than well. He comes to fetch her after work and presents her to his parents. His father greets her with a smile. His mother is more wary. Alison was to get on wonderfully with Daniel’s elder sister Patricia, who she still sees even now. In the evening, his mother makes up two separate beds for Daniel and Alison who wait until everyone is asleep before getting together like two secretive children. On Sundays, Daniel is sometimes invited by Alison’s parents to share in the traditional family roast beef. He’s not quite the ideal son-in-law, but he’s on his best behaviour. He talks amiably and impresses them with his pleasant attitude. He spends hours chatting about this and that with Alison’s mother. He has an evident taste for commonplace, everyday things, as if this normality at his fingertips is what he’s always aspired to. A family, a quiet little life, maybe some kids: among the 1001 lives on which Daniel Treacy fantasises, this one has always hovered around him without ever managing to draw him in.

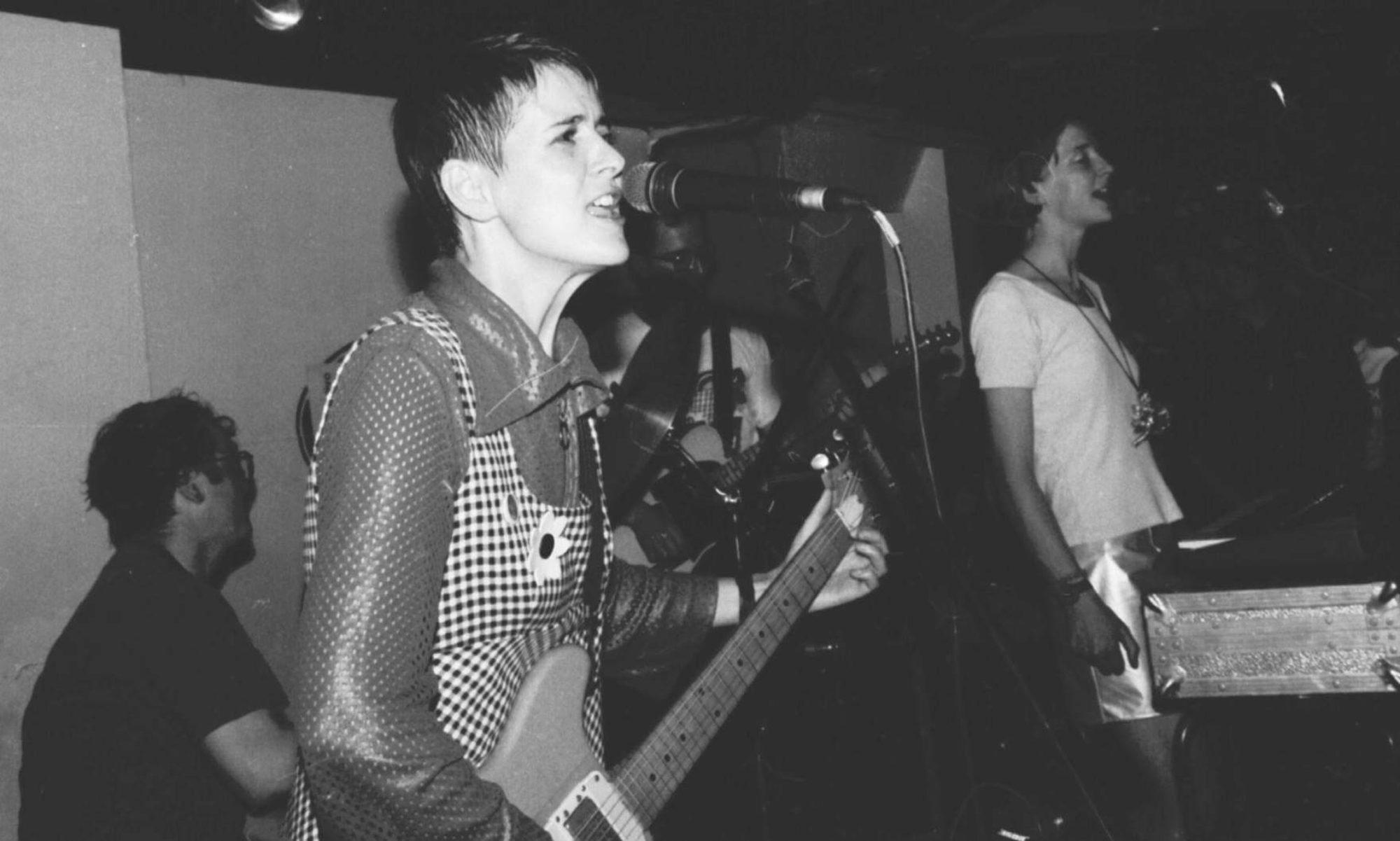

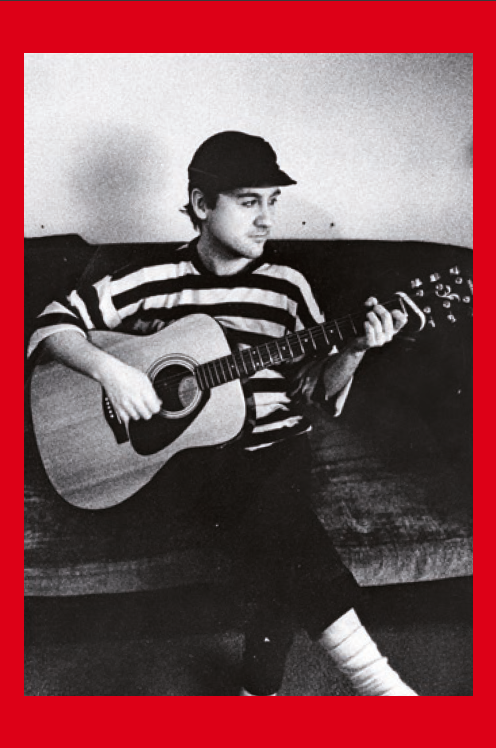

In the summer of 1989, they move into a three-room flat near Acton Town in West London. It’s an old block, built in the 30’s. They do some refurbishing, such as painting the entrance hall black and white. They have come into some of Alison’s grandmother’s furniture, as she has just died. Daniel begins to relax a bit. His drug habit is reduced to a few doses of speed on days when there’s a concert. One day, Daniel comes across a strange bag forgotten on a tube train. Inside is the equivalent of three thousand dollars and five American passports in exotic names, two pairs of binoculars and a very expensive camera. From what he would relate later, the bag was just there at his side. It’s not theft. The bag was calling for help. Daniel takes it and gets off the tube while it’s coming to a halt. Officials arrive and seem to search the carriages and inspect the platform. Daniel makes off. Opportunity makes a thief. The money soon disappears. It slips between his fingers like a fistful of sand. But there’s still the camera, and it determines Alison’s career. Librarian and photographer from now on. The young woman takes her inspiration from pop art, does photos and collages. She goes to night-school. Like Emilee Watson before her, Alison becomes the graphic artist for the Television Personalities. Daniel encourages her with a sincere fervour. He encourages her to take the plunge and enrol at the School of Photography near Paddington, after leaving her job at the library. Alison lacks confidence, but her work gets better and better.

Alison excels at portraits of her boyfriend, group portraits and background shots. How many sofas, pale walls, pseudo landscapes, held up behind the tour bus, peanuts and aperitif tables? Pullovers, jackets, bonnets, whatever you like. Her approach is both distant and eager to grasp everything that is sensitive in humanity, in a corporal pose or the flash of a look. It’s not an insult to other photographers to say that Alison “Wonderland” Withers is the photographer who has best captured what there was of poetic, beautiful and sometimes sadly dark, in Daniel Treacy’s features. You only need to look at the dozens of photos scattered about on the Net to realise it: she created the mystery just as much as she was to reveal it during the seven or eight years over which they shared everything. For the band’s record sleeves, Daniel often gives the impetus, the initial idea. Alison develops and exploits it. One of their greatest successes is the collage made for the jacket of the single Salvador Dali’s Garden Party, which they compose lying on the floor of their flat while their cat Madonna rolls itself in the photocopies. Daniel never stops praising the “little works of art” produced by his girlfriend, which he would immortalise in the song of the same name.

There had been Emilee Watson and the flat at Poynders Court. From now on it would be Alison and Daniel, caught up in the eternity of these seven years from 1988 to the middle 90’s.

The chronology wavers between the fits of depression, the moments of stability and the air-pockets. It comes in seven-year cycles. Such is the curse. At the ages of 14, 21, 28 and 35. The next one would be devastating, but there’s still some time for happiness and love between the couple. Love is a breath of fresh air. You take refuge in your own little world. Failure is knocking at the door and addiction lurks under the carpet. The flat is a nest, an oasis, small, comfy, held together by the colours, the dreams, the piles of books, drawings and music. The main room is a workshop, based on the inevitable sofa seen on dozens and dozens of photos, on the kitchen table, which doubles as a desk, a workbench for cutting out and preparing the material, a place where they sit and work or just daydream.

Daniel and Alison would keep cats, two most of the time, called Madonna, Andy Warhol or, later on, Orangina. Sometimes their contribution is acknowledged on the record sleeves. Daniel plays the guitar, thinks up songs and writes. He writes texts which gather dust in shoe boxes, poems, dozens of pleasant little notes, short and lively like haikus. He sketches out of happiness. He plays records, reads books. Together, Alison and Daniel watch old British or foreign films, on VHS cassettes bought at the supermarket or second-hand, mainstream programmes or series on TV. They cook with Keith Floyd, the celebrity presenter at the time and gorge themselves on children’s programmes and sitcoms. The Brittas Empire is one of their favourite shows. The series relates the life of an incompetent manager. His ideas are mostly halfbaked and his life is boring. His wife has affairs, or swallows pills to keep her head above water. Gordon Brittas’s deputy suffers from allergies. The receptionist is nuts and keeps her children in the drawers of the reception desk. The series is spectacular and wacky, absurd and slightly cynical. The Brittases are everything which Alison and Daniel will never be. Most of the time, Alison calls Daniel Treacy Mister Brittas. They like the humour of comedian Vic Reeves and his show Big Night Out, which alternates silly sketches and more serious items.

They play board games, frequently matching themselves at Mastermind. Daniel is clever at working out the combinations. He has kept the logical agility of his youth. Black and white key pegs for yellow, green and blue code pegs. There is a complexity and at the same time an inevitability in the trial-and-error approach and in the deduction which makes you think that one day, life will be as simple as the game. You just have to eliminate all the possibilities and have a bit of luck. Mastermind is an allegory of life: you make of it what you can. You reach your goal in one or two guesses, or miss your objective by a move or two. Everything comes down to that: getting there too soon or too late.

Daniel is the sort of guy who never arrives on time. It’s best not to expect him at a rendezvous. Alison and Daniel nevertheless fix thousands of them. She starts by waiting. Then she gets into the habit of guessing when he’ll arrive. She deliberately turns up late. It’s their little unconscious game. It’s obviously much easier to go out together and to leave at the same time so as to be sure of not missing each other.

The two of them go out a lot. There are concerts, of course, usually two or three a week. Alison and Daniel go to the Camden Falcon or the West Hampstead Club, the Laurel Tree or the Boston Arms, pubs and clubs which they frequent. They like to discover new bands and keep in tune with the vibrations of the audience when they first hear an up-and-coming band more talented than the others. Daniel would never lose this curiosity. After the concerts, they often finish the evening, although not systematically, with a few jars down at the pub. Daniel and Alison aren’t keen on parties and are more inclined to spend quiet evenings at a restaurant or in a bar, rather than haunt the night clubs. They have their good addresses: the Stockpot, the Brompton Troubadour, the New Piccadilly or the Honey For The Bears (one of the Television Personalities’ titles) in Acton. Their flat is at 37 East Vale on Second Avenue. They live there for two years before moving to Cambridge Court on Amhurst Road near Finsbury Park in the autumn of 1991. They eat Indian food, good or bad curry, or Mexican dishes in restaurants in Camden or Soho. In London you’re spoiled for choice. Daniel and Alison walk all day long when they are alone together. They like romantic strolls, psycho-geographical walks where you discover the hidden treasures of the town. They linger around in Ravenscroft Park, in cemeteries like Brompton or Old Highgate Cemetery, where Karl Marx and George Eliot are buried. They follow the banks of the Thames near Hammersmith Bridge and explore the East-End back streets between Whitechapel and Liverpool Street.

Daniel and Alison are real townies. Hand in hand, they scour the record shops, flea-markets and charity sales. They know the markets well, and rarely go out without coming across people they know. They never miss a pop-art exhibition and go to the La Scala cinema. Swinging London belongs to the past, but London still vibrates to the rhythm of pop and culture. Their world is full of friends and relations who work in the sphere of the press, music, art: failed intellectuals, booksellers, former or future members of the band. There’s Jowe Head of course, but also Ed Ball who is never far away. Alison avoids certain Television Personalities’ fans who gravitate around Daniel and share bad habits with him. Over time, Daniel has become used to not being successful, and to his position as an outsider, revered by “those in the know”. He can see the admiration in their eyes and takes a certain pride in it, which more often than not, he drowns in self-depreciation and alcohol. Between 1988 and 1995, Alison and Daniel’s life is more a romantic than a bohemian one. Money is short, but the couple live modestly and feed on culture. When they’re not going out, they eat a TV dinner off a tray. Daniel is now a vegetarian. He likes to joke and make love in the afternoon. He’s a shy man but he explores his lover’s body with the same serious attention as when he plays the guitar. Daniel is an intelligent man. He likes to stay in the background and do things discreetly, which is obviously a far cry from his exposed position as a singer. But his opinions are sound and often biting. He has a lively political awareness. He likes to support his friends, is generous and a brilliant imitator of singers or public figures.

In the strange life-cycle of the Television Personalities, everything isn’t hunky-dory in those years. The songs bear witness to the presence of spectres, of shadows that take possession of the singer and cloud his mind. But the darkness has ebbed, and love keeps it at bay. Alison and Daniel’s flat is like a sanctuary, a bulwark against doubt and evil. The exclusive relationship which he has with the young woman is what keeps him whole, keeps him together, prevents him from sinking and giving in to his self-destructive bent.

If someone loves you, it means that you are loveable, whatever you may think. We are all what others see in us. You don’t need to be a great philosopher to know that. Life is good, but not for long. These eight romantic years would be a storehouse of happy images, of memories and regrets for the years to come.

This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book Dreamworld Or: the fabulous life of Dan Treacy and his band The Television Personalities written by Benjamin Berton. © Ventil Verlag UG (haftungsbeschränkt) & Co. KG, Mainz, 2022.