Excavate! The Wonderful and Frightening World of The Fall

Edited by Tessa Norton & Bob Stanley (Faber Books)

The Fall were the first so-called ‘indie’ band I ever liked. I would love to be able to say that I came across them on John Peel or on a cool mixtape. In fact, it is on Top of the Pops, or more likely its rival, The Chart Show, that I catch the video for “There’s a Ghost in My House”, first encountering the Mark E. Smith sneer as he dodges china hurled at him by Brix, playing the eponymous grinning sprite. This isn’t early Fall of course, although perhaps that’s relative, given that the band still has more than thirty prolific years ahead of it. But in April 1987, the pop sensibility that Smith’s Californian wife has brought to the band’s abrasive sound is paying dividends. The Fall have never sounded more conventional, but they are still like nothing I have come across before.

“There’s a Ghost in My House” doesn’t feature prominently in Excavate!, Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley’s engrossing new collection of writing and ephemera on The Fall. In fact, the editors have little interest in providing a comprehensive account of the band’s long and turbulent history at all. Instead, with an approach more philosophical than biographical, each contributor to the text comes at the band according to their own interests and expertise, less interested in what the band did than at getting to the heart of who they were. Architectural historian Elain Harwood introduces us to Mark E. Smith the psycho-geographer via a tour of Prestwich, the North Manchester town where Smith lived all his life. Designer Paul Wilson explores the Northern Working Men’s Clubs in which the band played their early shows and ponders the influence that these venues may have exerted on their text heavy artwork. Bob Stanley, whose own band happens to be named after a football team, uses the football leagues as an avenue to discuss The Fall as amateurs (and, circa “TaGiMH,” as professionals).

A real pleasure of the book, one that speaks to the care of its editors, is how the varied contributions combine to unfold as a cohesive and satisfying whole. Occasionally the book format provides an avenue for writers to interact directly. Michael Bracewell & Jon Wilde’s essay on Mark E. Smith and Stuart Bertolotti-Bailey’s on Vorticist co-founder Wyndham Lewis playfully mirror one another. Continuing on the subject of Smith’s literary influences, a reprint of the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s Memorex for the Kraken considers the group’s early output alongside modernist and horror literature. Fisher’s essay quotes Mark Sinker repeatedly, and the latter writer here continues the conversation, responding to Fisher with a new essay of his own. Through these and other entries, we are guided from Smith, voracious reader and autodidact, to the group as an education in its own right. Tessa Norton considers The Fall as a curriculum, situated within a lineage of artist-led alternative educational establishments that include the Black Mountain College and Joseph Beuys’ Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research.

Of course, The Fall’s outsider status is never in doubt. There is Mark E. Smith the personality, who disliked the company of musicians socially and kept them on a tight rein within his band, who at the height of Madchester famously claimed Salford as his home, while decamping to Edinburgh until the fuss died down. Then we have Smith the visionary, who “when the Fall began,” quotes Ian Penman “was picking up the past and the future on different frequencies to everybody else.” And no one else ever quite matched their wavelength. In the essay most concerned with the Fall’s influence, Adelle Stripe doesn’t discuss Pavement or Prolapse, instead focusing on a mixed-media art project. For his part, Mark Fisher locates a shared essence between The Fall and the black comedy series League of Gentlemen in their predilection for “grotesque humour.”

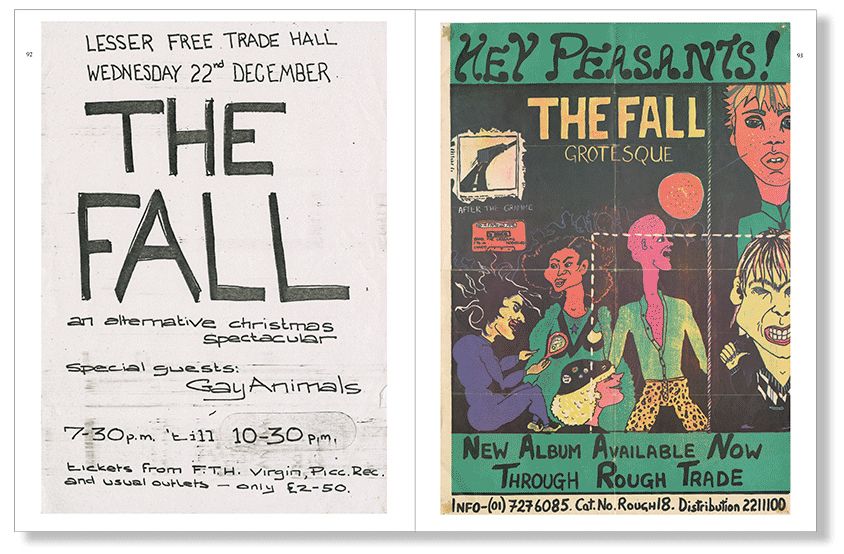

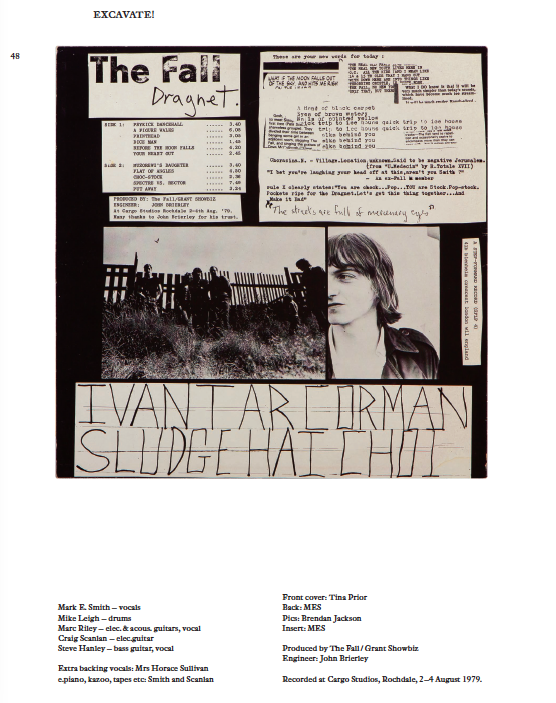

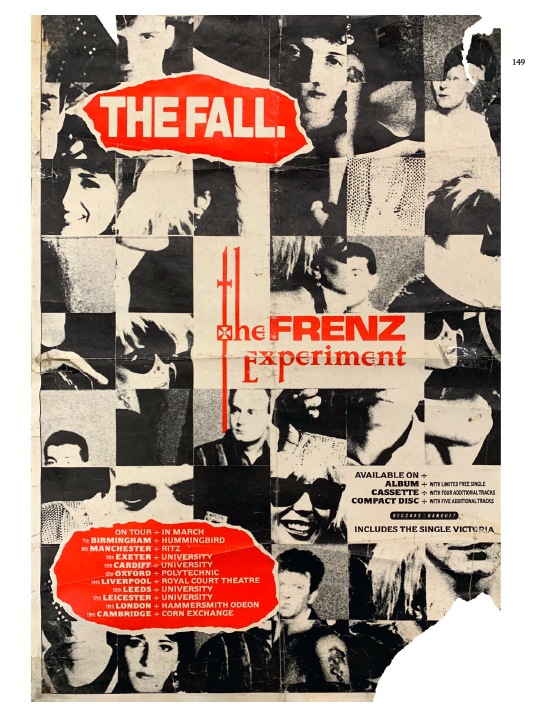

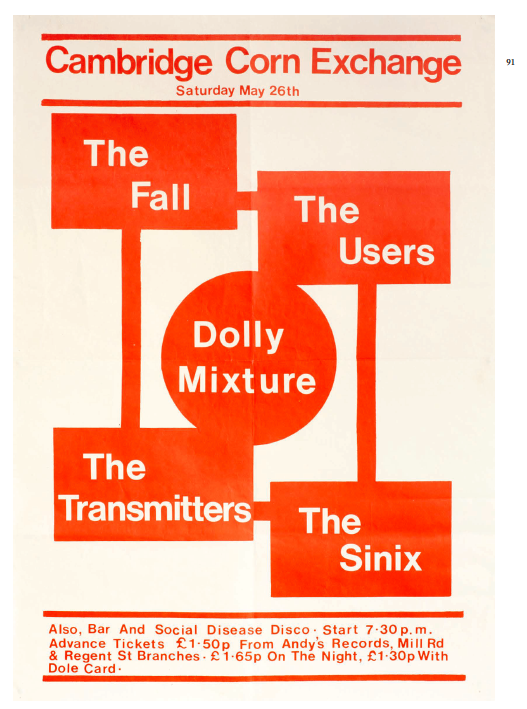

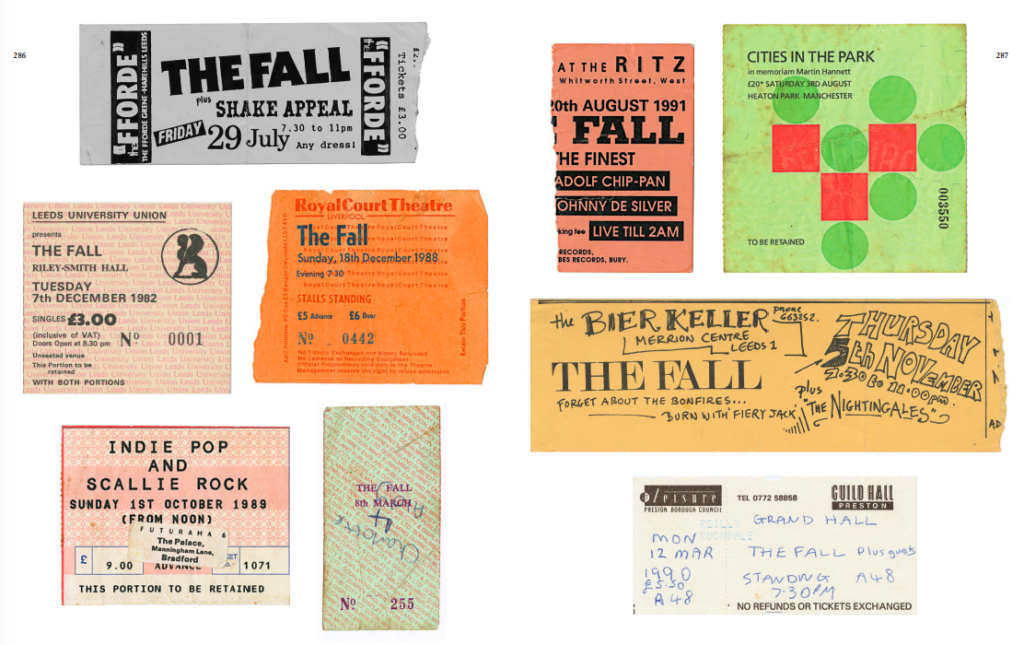

A second form of excavation bookends each of the essays. A cornucopia of Fall ephemera has been unearthed for the book, all drawn from the collections of fans. There are posters, press releases and fan communiques, song lyrics and notes on album track listings (“From the book, don’t read it,” Smith comments on Dice Man, a useful reminder not to read all inspiration as endorsement, especially from a writer so fond of the third person). The concert program for The Fall’s ballet collaboration with Michael Clark is included, as is an excerpt from Mark E. Smith’s original script for his play, Hey! Luciani. This is not written on beer mats, as sometimes rumored, although a scrawled-on beer mat is found elsewhere. It has all been lovingly cared for and is beautifully reproduced, along with the artwork for all thirty-one of the band’s studio albums. There is ample material here to reward the serious fan’s careful attention, but its handsome presentation within this hardcover edition also makes the book ripe for the coffee table, a designation that might have prompted some wry amusement from its subject matter.

I never had a big breakup with The Fall. I considered them my favorite group for a few years, and I always considered myself a fan. They were the first band that I ventured to see twice in a single week. One show was thrilling, the second a chaotic mess, the difference itself feeling very much in keeping with this group. At some point in the mid-nineties my attention began to falter, I still had my old records, but I barely noticed as new albums arrived. Inevitably, reading Excavate! has encouraged new excavations of my own, discovering Fall songs that I’ve missed, and breathing fresh connections into old favorites. “There’s a Ghost in My House”: An entwining of Smith’s embrace of Arthur Machen and America music, a Motown cover from a band whose signing to a Motown subsidiary was scuppered by a regrettable lyric in the 1982 song “The Classical.” A music book like none I’ve encountered before, Norton and Stanley have assembled a fine tribute to one of British culture’s most idiosyncratic voices. Excavate-ah!

—Chris Phillips