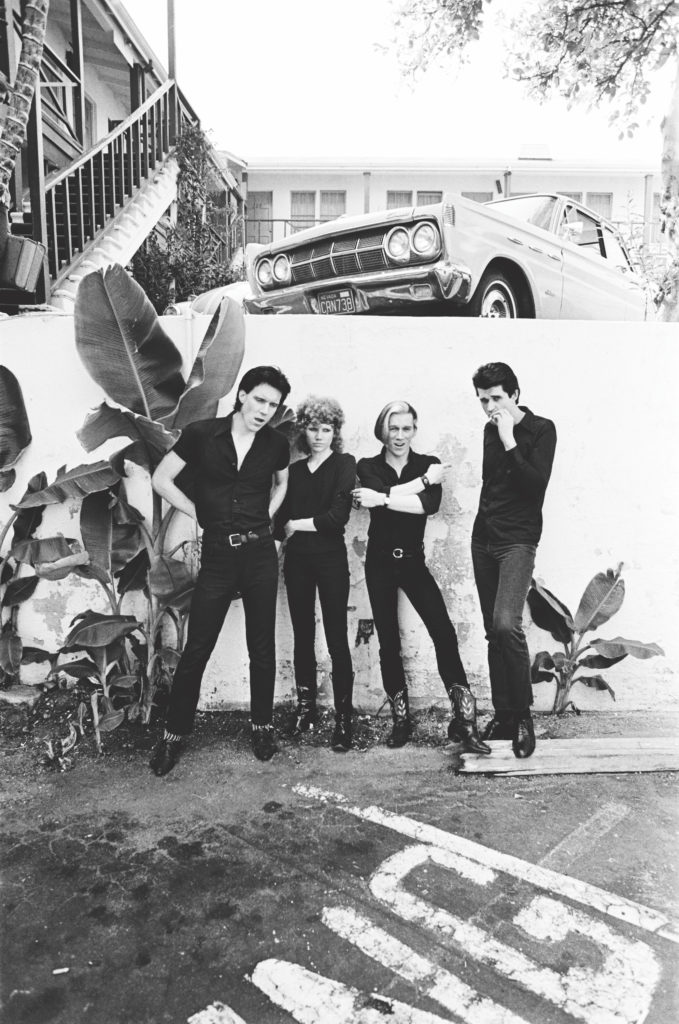

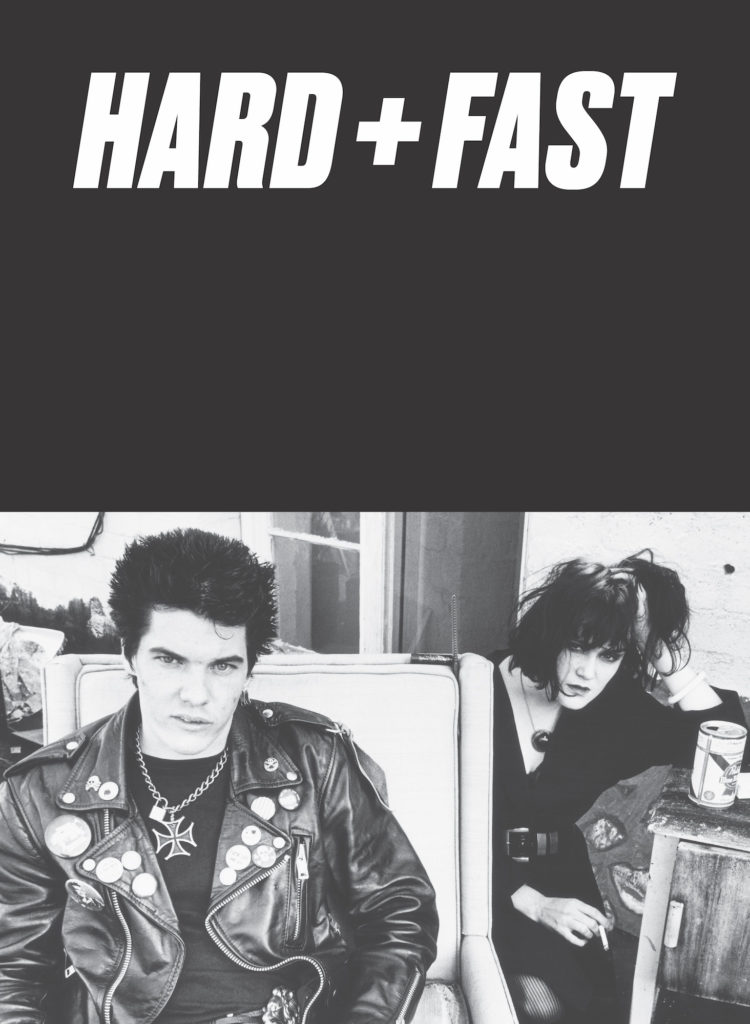

HARD + FAST, a collection of Melanie Nissen’s photographs from the period 1977-1980 in Los Angeles as punk was forming, is the book my OG LA punk friends and I have always wanted to exist. We all knew that we were living in a special time when you could see culture and society changing, and we couldn’t wait to document it ourselves. It was an era rich with samizdat—independently published zines about our scene, shown and told in our own words and pictures. Mainstream media were not covering the epochal change in pop music, art, and fashion, save for the occasional “look at this crazy new teen fad” filler on tv or in print. ¶ Our subculture took it upon themselves to document our own lives, much like a high-school yearbook does. Melanie, together with her then-partner, Steve Samiof, created SLASH, an era and genre-defining magazine with such an imprimatur that it organically grew into an avatar branding first wave punk. Melanie’s book of photographs overflows with the love and friendships that we LA punks shared, and yearbook/time capsule references to this important documentation is a recurring Proustian theme in this 2022 chat between two zine photographers. Intro and interview by Theresa Kereakes (who was also documenting the scene back then) / Photographs by Melanie Nissen

REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST

CF: A lot of the things that I like about the book have nothing to do with punk rock, but everything to do with presenting a chapter of our lives that we lived at the same time. There are buildings that you photographed that are no longer there.

Melanie Nissen: I have to say that’s what the book has become for me. I look at it the same way. It’s become documentary to me. You don’t see people on the street selling LA Times newspapers anymore [p 98, with Tommy Gear/Screamers]. You don’t see people on phone booths anymore in Hollywood [p 108/Tomata duPlenty/Screamers]. You don’t see old pool halls where you could just go into, or old eating places that were on the street, and old bars that existed that don’t exist anymore. For me, it’s like a time capsule. I think I really appreciate it on that level. And I’m really sentimental about it on that level, because I felt the same way that you did. You just don’t see this stuff anymore.

CF: It’s like a yearbook.

Melanie: Exactly. That’s how I feel about it now. I can look at the photos and it’s so funny, and you’ll probably relate to this—I can feel when I took that picture. I remember. I remember where I was. I remember how I felt. I remember taking the photo. I remember everybody’s face. I had a hard time with everybody’s name for the book, but I never forgot their faces. Ever. Everybody was, I think, really open to me taking photos and I really appreciate it.

ART FOR ART’S SAKE

CF: Did you know when you were in the midst of it, that punk was going to be the transformative movement that it became?

Melanie: Not at all. It was a very unusual time. It was like this big art group that all decided to pitch in and work together. It wasn’t really about anything else except the music. It was very unique that way. It’s so seldom that you get to have freedom in art, and that’s what it was to us—to show anything we wanted, say anything we wanted in the magazine. That’s a luxury in art. Those opportunities don’t come around a lot when there really aren’t any politics there, there’s nothing, money’s not involved, it becomes just a real art project. But no, I didn’t know at the time. I didn’t even take very good care of my negatives to be really honest with you.

CF: I’ve talked to a couple of other people from the scene who just really put this stuff in the garage and it’s like, “Well, this is my stuff from the ’70s.”

Melanie: That’s what it was. Except unfortunately, I had three really bad floods in garages.

CF: So have I.

Melanie: Did you, too?

CF: Yes. I lost a lot of stuff in Hurricane Sandy. I moved to New York in the ’80s.

Melanie: Yikes.

CF: I was really devastated then I heard an interview with Laurie Anderson on NPR, where she was talking about the album she recorded with the Kronos Quartet, called Landfall, which was about everything that happened in Hurricane Sandy. And she had lost basically, her entire professional life: staging, work, all of her props and a lot of notes and stuff.

Melanie: Oh, God.

CF: But her voice was so calm. And I thought, “Well, if Laurie Anderson can get past this, then I can.”

Melanie: Well, I did too. But at the time, it’s like you think, “Oh, what a bummer.” Then you just get over it and I think, “Well, that’s it.” Because I didn’t even really know if I would be using my photos again. Do you know what I mean? They were in bags. I didn’t really know I would be actively using them. I didn’t want them to get ruined and it was disappointing when I looked at them, but it’s like, okay, well, so this is what I have left. You move on.

CF: Right. In the spirit of that, is it astonishing for you to see the legacy and the influence of Slash, just from the graphic style to the writing style?

Melanie: It is. Steve Samiof was my partner at the time and we started it together. I think the very first issue, I really think it was the consciousness that we’re going to do a one-off art magazine. I really didn’t think we thought we would do more issues. I don’t know if we really thought it would go further than that. So it was a big surprise. We had read all about all the punk stuff happening in London and we were fascinated, because there wasn’t much of it here yet. So we went to record stores and bought every single we could possibly buy, and had to come home and listen to everything over and over. ¶ It’s like we both fell in love with the music, with everything about it. Everything about it was appealing; the fashion, the politics, everything. But did I think it was going to go on and on? No, I didn’t.

CF: Yeah. We were just not like other people and we didn’t fit in anywhere, but we all fit in with each other.

Melanie: Well, it’s funny. I have to say, everybody asks “Oh, what was it like?” And really, everybody for those three years that I worked with, was on the same wavelength. Everybody was generous with their work. Everybody helped everybody else. Every band helped each other. Everybody gave free work away for the bands to use.

CF: I read a quote of you saying, “The first three years were magic, but by 1980, Orange County bands started taking the scene in a direction I didn’t love.” I related to that so much because I felt the same way. I don’t know if you doom-scroll Wikipedia, but the entry for Slash in Wikipedia, have you read it?

Melanie: No.

CF: It’s like a paragraph, but it conjectures that Slash just stopped because punk was considered dead anyway. But I relate to your quote, “the bands started taking the scene in a direction I didn’t love.” That makes sense to me.

Melanie: Yeah. I also didn’t know them. I really didn’t know who they were. I can’t think that I have photographed a lot of them. It’s like I had spent three years with the same bands and all the beginning bands. It’s like it becomes a weird family in a weird way. Nobody cared about me with my camera. Everybody was used to seeing it. We would do photo sessions on the street. We’d never get permits or anything like that. It was very spontaneous. I don’t know. I just think after three years, all my favorite bands were going away. They weren’t really playing anymore. They all were off in different directions. ¶ Then you had the Orange County stuff, and I just didn’t know it. I just thought it was time to move on. I had been in it a lot and it was just time to do something else for me.

CF: Do you agree with this: Slash as a magazine is a finite set, it’s like it’s a box set of LA punk rock being born, it’s almost like you inadvertently created LA punk. So, your book is its title. It’s just 1977 to 1980. Hard and Fast, in and out. This is a box set of that period.

Melanie: Yes.

CF: Did you intend to do it, or did you set the book up that way because that’s what you had?

Melanie: I only was in it for those three years, so that’s really all I have to talk about. I don’t have anything to really say about punk. Your life moves in a different direction sometimes, and that’s what mine did. I had a full-time job.

CF: I was just going to ask you that. Did you and Steve and everyone else for the core of Slash, did you keep your day jobs?

Melanie: Well, I had to. Steve’s day job was Slash, which it needed to be, because it needed one really strong leader that was there every minute. And he was that person. I worked full-time and I have a daughter. It was a lot. I used to go in the dark room and print all my own prints on the weekend. Yeah. It was a lot of work.

CF: You bring back all these memories for me, flipping through your book; that image of the envelope from Richard’s Photo Lab [p 217] !

Melanie: I know. Do you love that?

CF: I love that because I have boxes full of the same thing.

Melanie: It’s like everything was at Richard’s in the beginning. It was all at Richard’s. He’d develop it, and then I had access to a really great darkroom, which I was lucky enough to get on the weekends. So I’d have Richard develop it and then I would go print it. But that is funny, Richard. That’s where you went.

CF: One thing I really appreciate about your book that I haven’t seen in too many other punk photo books is that you’ve included Black Randy [p 62], The Screamers [pp 18-31], and The Kipper Kids [pp 112-113]. The Screamers were just so unique. And Tomata, before The Screamers, had quite a track record as a performer.

Melanie: Yeah. Yeah. How good was he to photograph?

CF: He was a living art project, right?

Melanie: He had the best body language and the best space and the best tattoo. I could have just looked at him forever. I could have photographed him forever. Luckily, a lot of that stuff of him didn’t get wrecked, and I’m so glad I have so much of that early stuff. He was really great to work with. ¶ And Black Randy was such an underground star in the scene. He got up and performed in his underwear and a cowboy hat. It’s like, who are you? Then I became one of his backup go-go dancers at one of his live shows with Belinda from the Go-Go’s, Alice Bag from The Bags, Connie. And myself. We all had wigs on and all this makeup somebody did for us and we had dashikis on. We were his backup dancers. ¶ Black Randy was in our bed while Steve and I were designing the magazine in our bedroom. He just got in bed and just talked to us. He was so weird.

CF: That’s this unique thing that only other people who were in that scene would understand. If you tried to tell someone Darby Crash was in your dorm, it’s like, well, they don’t understand. He was just a guy who I knew. And I had a TV and he didn’t. It was just that.

Melanie: I thought he had a very sweet side to him. Am I right or wrong?

CF: Yes, and I just thought he was really smart.

Melanie: I thought he was smart and I thought he was always … I don’t know. I thought he seemed like a really kind person to me.¶ Yeah. Everybody asks, “Oh, and what about Darby Crash? What was that like?” And I’m thinking he was really nice.

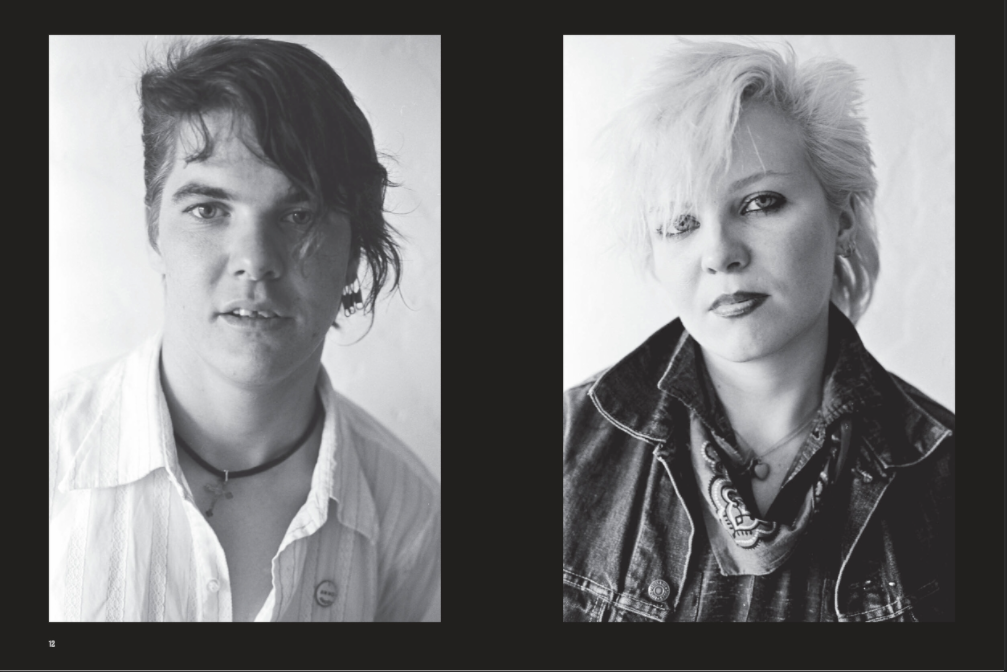

CF: You could tell that you were friends in the pictures of him and Pat and Lorna. There’s not a menacing glance. And the young Don Bolles, he looks like a little angel. [pp 12-17]

Melanie: I know. I know. I know. No, they’re pretty raw photos. It’s very more documentary than I thought it would be.

CF: Is that what got you the most? Is that when you went back 40 years later and you thought “this is a documentary”?

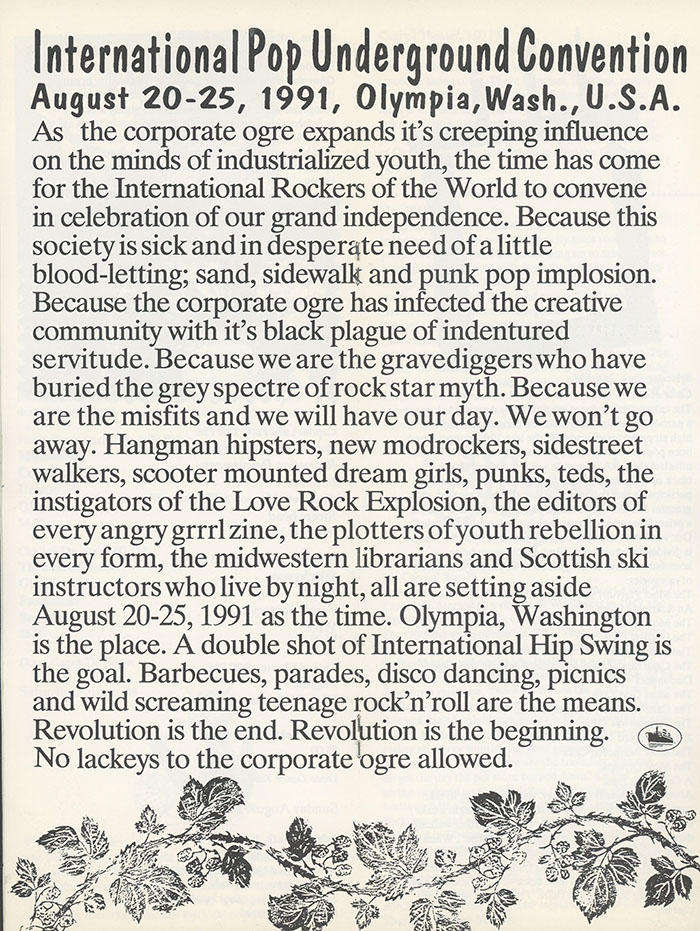

Melanie: Yeah. I thought it was a time capsule. I thought here is this one unique period of time in my life and everybody else’s life that was involved in that. And I’ll probably never see it again. This is not going to happen again. And there was that part of me that realized that part, that this was something very unique and wasn’t ordinary. I really appreciate it from that point of view. It was really fun and interesting and creative. ¶ The one thing that I find really interesting, is that it’s true, punk never dies. It never dies. It reincarnates itself. You see it in young bands. You see it in fashion. You see it in hair. You see it in jewelry. You see it in everything. Right now, it’s like hot pink and hot green DAYGLO, and black are the colors of the season. Well, that was punk. Those were the punk colors. And every once in a while, you see photos of chokers with big spikes on them, and then you have Marc Jacobs who’s looking at all the punk stuff. It just gets created over and over and over again, and I don’t really think that time’s ever going to go away, musically or fashion. It’s like Vivienne Westwood. She’s still making clothes. ¶ There’s a little band, a little punk band that was out there… Fidlar. I don’t know if you know them. They’re really good. They remind me a little of The Ramones. They were a very fun little band. You could just see it. And they knew all the people from the punk things. They’re really and they were totally into Slash. And I think, “Wow.”

CF: I’m glad to hear things like this, and like you publishing the punk rock yearbook, time capsule. And it brings everyone back together to say hello and wow, wasn’t that something?

Melanie: Well, and this is it for me. You know what I mean? I don’t have anymore. I don’t have a lot of punk to show anybody anymore. This is what’s left, or what I have.

CF: You know what? It’s still definitive. It’s the foundational visuals of LA punk rock. It really is.

Melanie: I don’t know. I hope that people get to see themselves in the book because it’ll be so fun for them.

CF: I think that they will, people will bring it up to them. They’re going to get a call from someone like, “Oh, my God, you’re in this book!”

DIY

Melanie: If I never have to go through another box again, I’ll be really happy. I’ll tell you, the hardest part of this whole project was just digging stuff out and editing. It was really, really hard. And getting stuff scanned. Nothing was scanned, at all. ¶ I wound up too, and I hope it’s not boring for people, I put a lot of fan photos in there, fans and people that hung out. They’re not stars or anything.

CF: I was so excited when I saw Cheri the Penguin [p 85] !

Melanie: I know. This was so part of the scene that I documented. It wasn’t just the bands. There hardly was anybody that I didn’t take photos of. And I thought, “Well, I’m going to put them in the book, even though nobody is probably going to know who they were unless you were there.” ¶ And is that going to appeal to people? Because basically, a lot of younger people would just be looking at strange people they don’t know. So I was a little concerned about that, but it’s like, how can you do the scene if you don’t do the people in the scene?

CF: It’s like you just said earlier. It’s a documentary. It’s how people dressed.

Melanie: Yes.

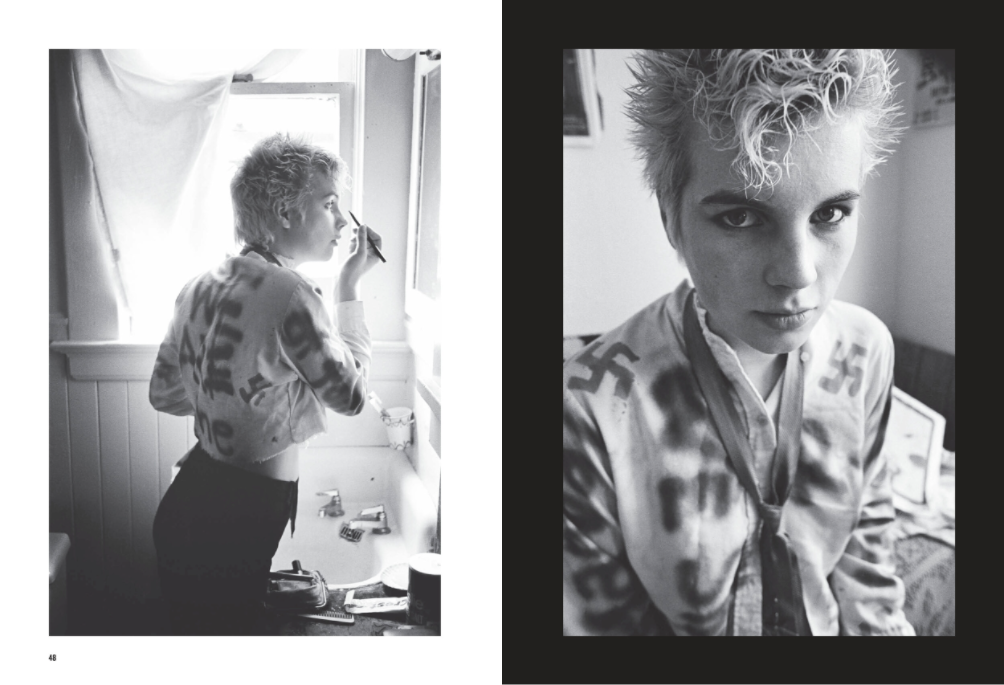

CF: What’s so great is that everybody had their own unique style. It wasn’t like they could go to a Hot Topic and say, “I would like the punk uniform for Saturday night.”

Melanie: Yeah. But you know what was great? They all made their own outfits. It’s like they had to plan. They had to make something. That was half the fun of looking at everybody, is to see what they came up with and what they created. It was really interesting, and everybody really made an effort for the most part.

CF: Yes. Do you think that has anything to do with because it was the analog era? You literally couldn’t phone it in. You had to make a commitment.

Melanie: Yeah. You did. There was nothing technical at all, right?

CF: Right, there wasn’t. I was envious of people who had motor-driven cameras.

Melanie: Yeah. And I was so happy to have access to a darkroom. I thought that was the height of luxury because there was nothing like being in the darkroom and seeing that image first come up. It’s so exciting, whether the photo is good or bad or whatever. It’s just thrilling.

CF: The smell of the chemicals.

Melanie: Yeah, which people don’t even use anymore. That’s why they really don’t want to develop black and white, because you have to get rid of those chemicals in a certain way now.

CF: Oh no, I know. But it’s just they’re gorgeous. And I like the way you printed your photos with the carved out negative carriers. You could see the edges.

Melanie: That was fun. I didn’t do that with everything, but I don’t know. I think for me at my age now and everything and from what I have left, this is like doing the last issue of Slash for me. Do you know what I mean?

CF: Well, what is the future? What do you want to do? What would you like to do?

Melanie: I don’t know. Well, I still take photos. Not a lot of people anymore, but I do a lot of abstracts and landscapes and all that kind of stuff. It’s different now. There are still artists that I work with because I went into the music business for the rest of my career and life. So I always wound up working with musicians, forever, which I felt really well-suited for after Slash. And that I get it and I get them, and they get me.

CF: How did the book come into being, finally?

Melanie: I have a friend who designed the book. His name is Mike Lohr. We have been friends for like 20 years, and we have a wonderful friendship and rapport. When we thought about doing this book and was asked to do the book, I said, “There’s only one person who I’ll do this with. And it’s Mike, because he’s such a beautiful designer.” ¶ We did a series of weird punk T-shirts at one point and tote bags. We never did anything big. It was all little and nothing ever made any money, but we liked working together. So when this book came along, we had a chance to do a book together. ¶ Half of the project was that for me, that I got to work with Mike. And we worked together for almost, I don’t know, three, four years on it because he has a full-time job as an art director. We were limited to maybe two weekends a month, one weekend a month, so it took a long time. But I was so happy I got to work with him. It’s like our culmination together, and it’s really nice.

PARTING GIFT

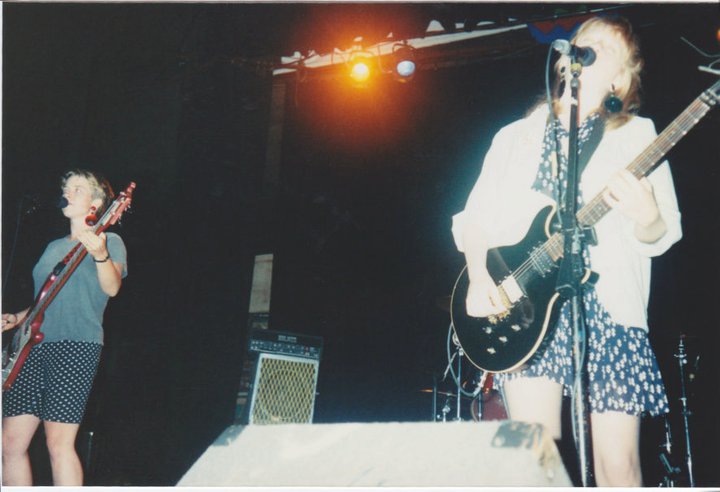

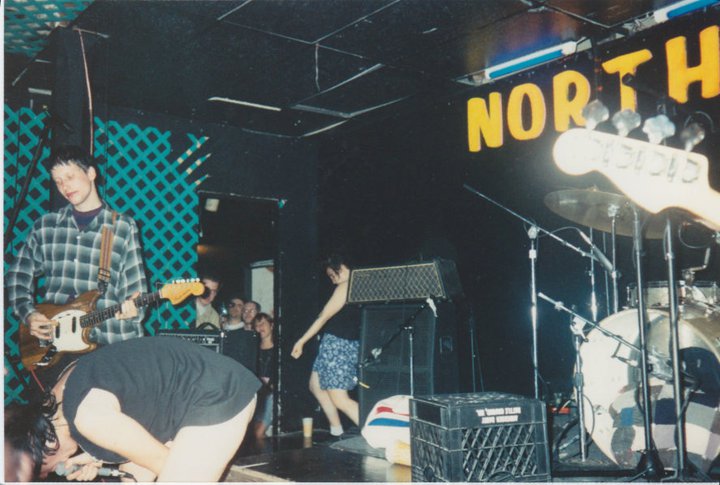

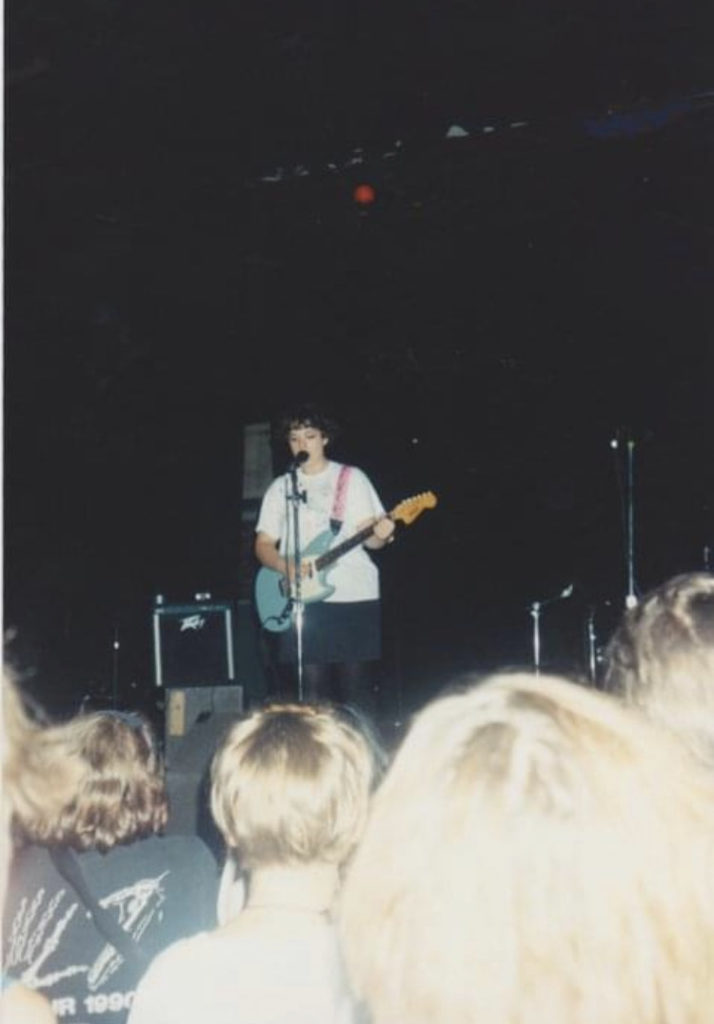

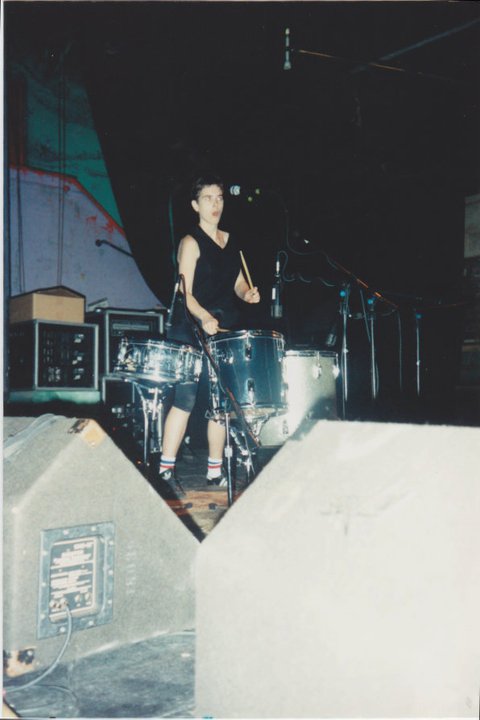

Melanie: I’ll tell you one thing that I had to learn that was very interesting for me. I had never shot concerts before. I had never shot music, and I had to learn how to shoot the bands live. I had to learn how to get up front, no matter what was happening or who was shoving who or pushing who. I was very fast. I shoot very fast, and I think you have to if you’re shooting live. I don’t know how else you get it, really. It was really a great challenge for me to have to do something new like that, and learn something new like that, and practice. I got better as time went on, but it’s something that I really valued that I thought, Oh, I have a split second to take a photo up here. Everybody’s shoving me and I have to do this. I have to get a good photo. I have to get something. And I loved learning that. That was a very good learning experience for me.

CF: I think it’s all in the learning.

Melanie: It is. Everything.