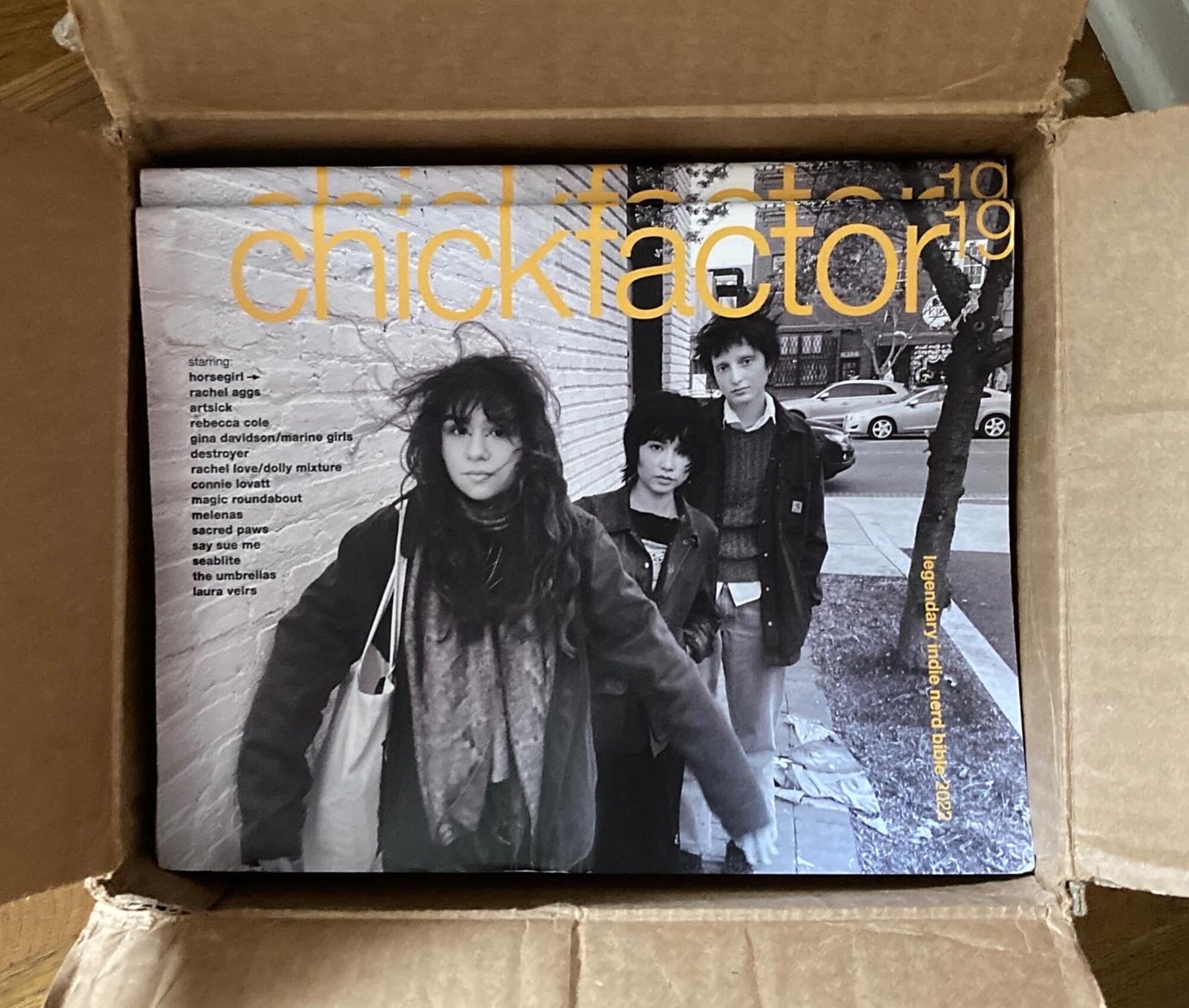

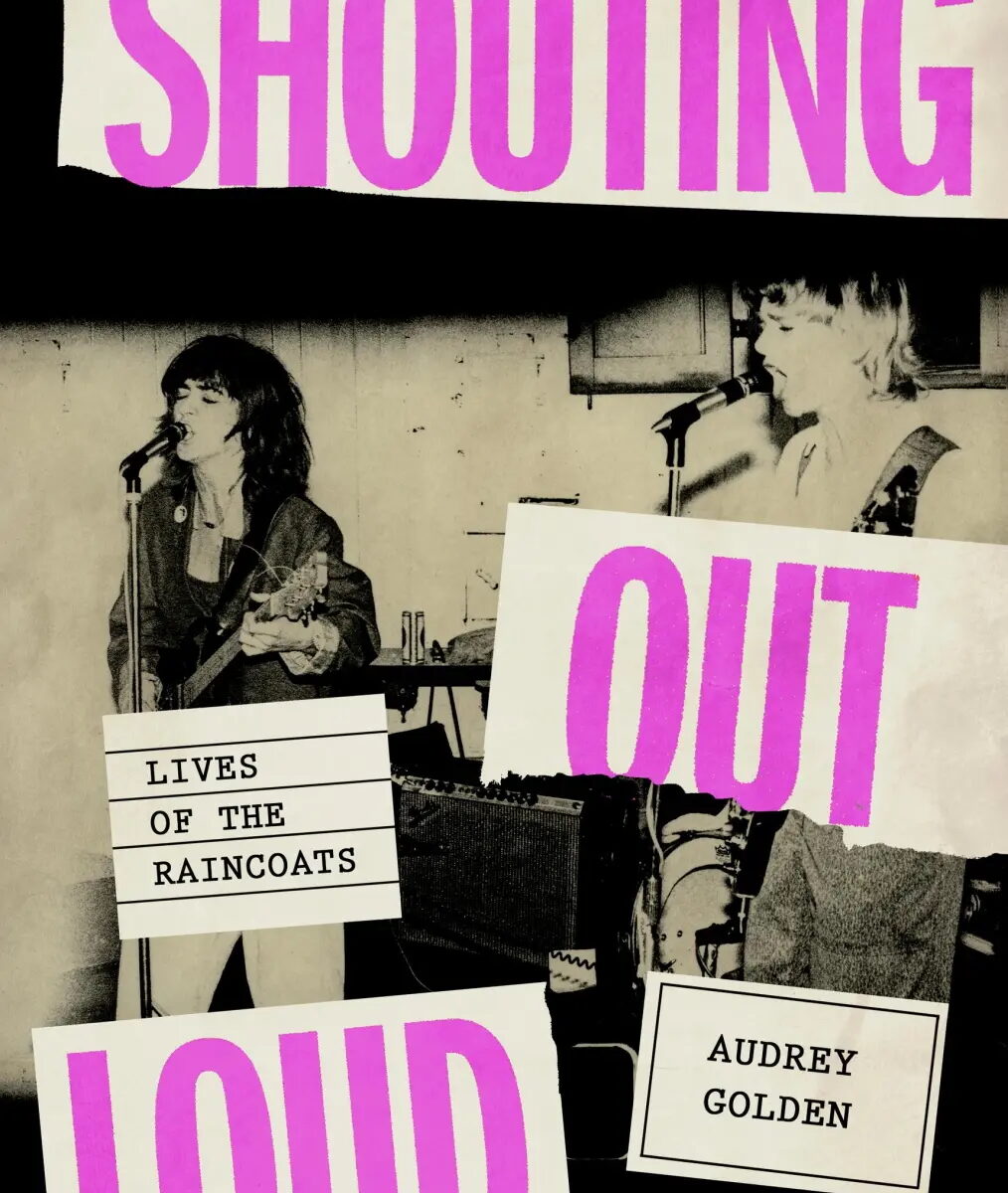

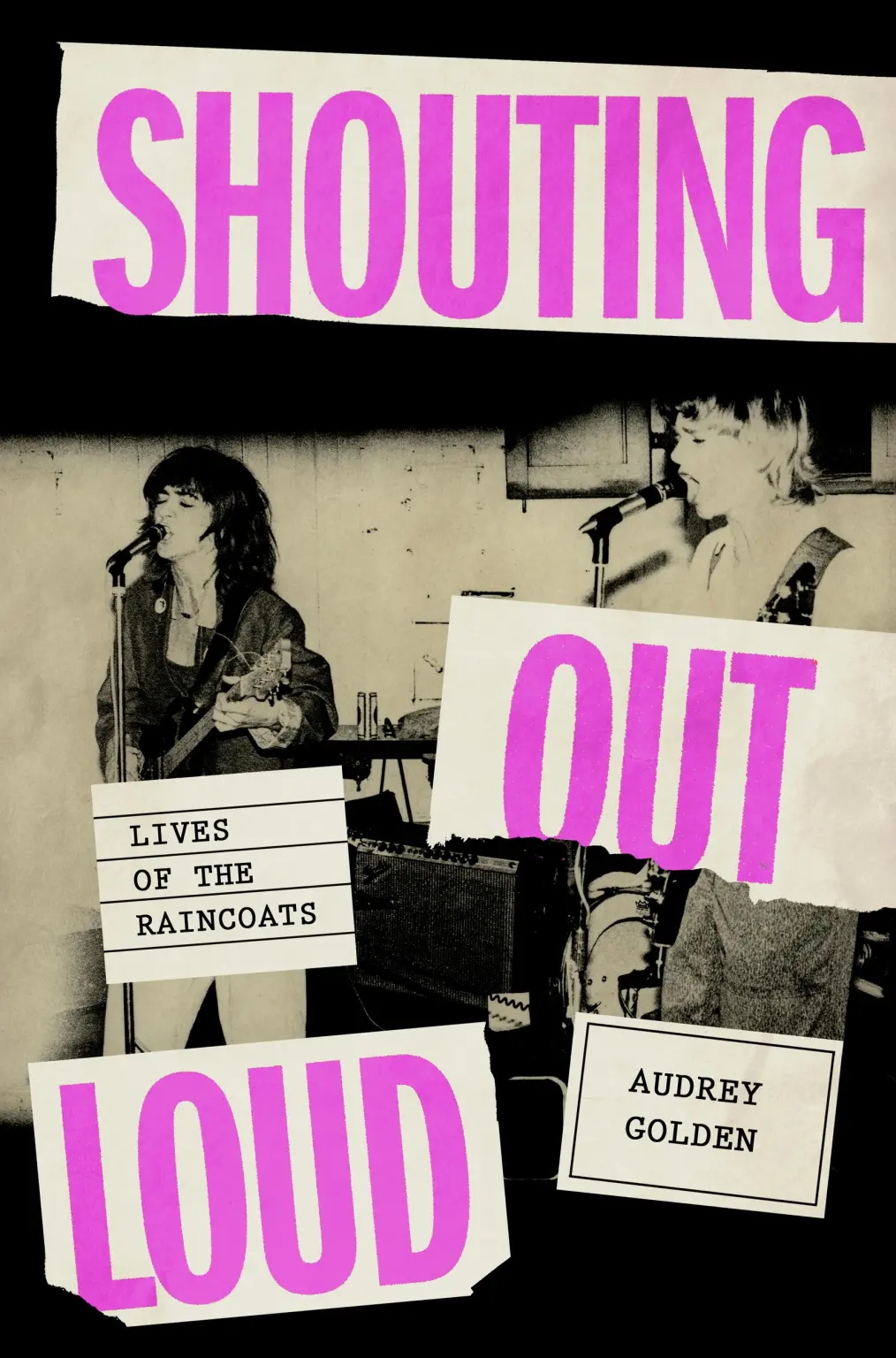

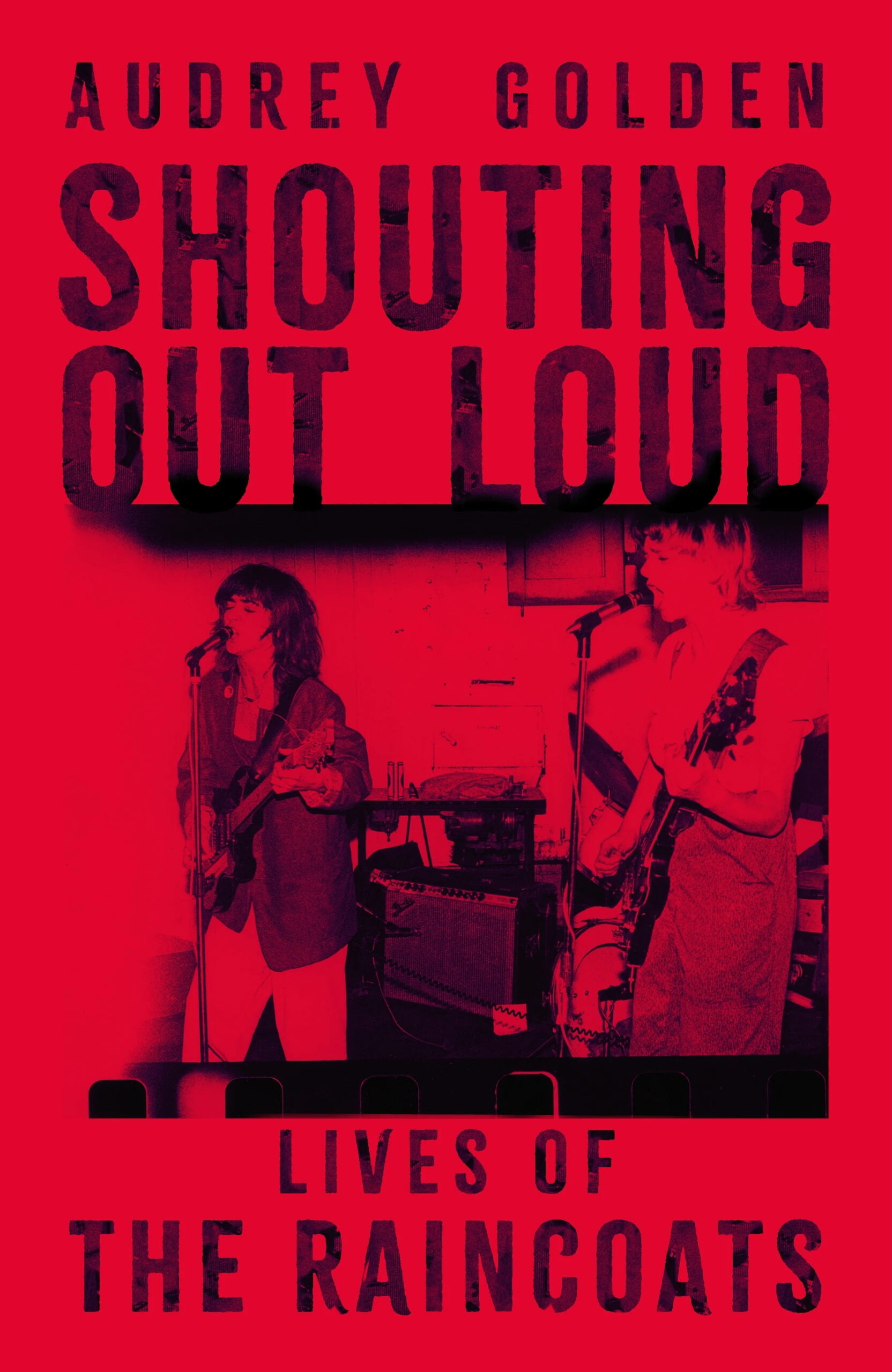

We are thrilled to present an excerpt from Audrey Golden’s new book SHOUTING OUT LOUD: LIVES OF THE RAINCOATS: Read three sections from the book’s midsection about the impact the Raincoats’ music had on Olympia, Washington, in particular. It’s a wonderful snapshot of how we all discovered music in the pre-internet (basically) era and it shows how bands like the Raincoats exploded the notion of what it means to be punk.

US folks can order here – out July 15

UK folks can order here – out July 31

Or come get a book at one of Audrey’s book events next week:

July 17 Seattle: a book reading and a Raincoats sing-a-long at Hex Enduction Records in Seattle as part of Art Walk!

July 18 Portland: Come to Powell’s Books for a book launch event featuring Audrey, Corin Tucker, former Raincoats U.S. manager Sheri Hood and Gail O

July 25 NYC: Book talk and signing at Rough Trade Below in NYC

July 31: MassMoca book event

LIFE NUMBER 2

“We realized eventually that in the United States, that’s where we had the most people interested in what we do, and where we had the biggest influence,” Ana says. And so, in the rainy musical wilds of America’s Pacific Northwest, The Raincoats’ second life began.

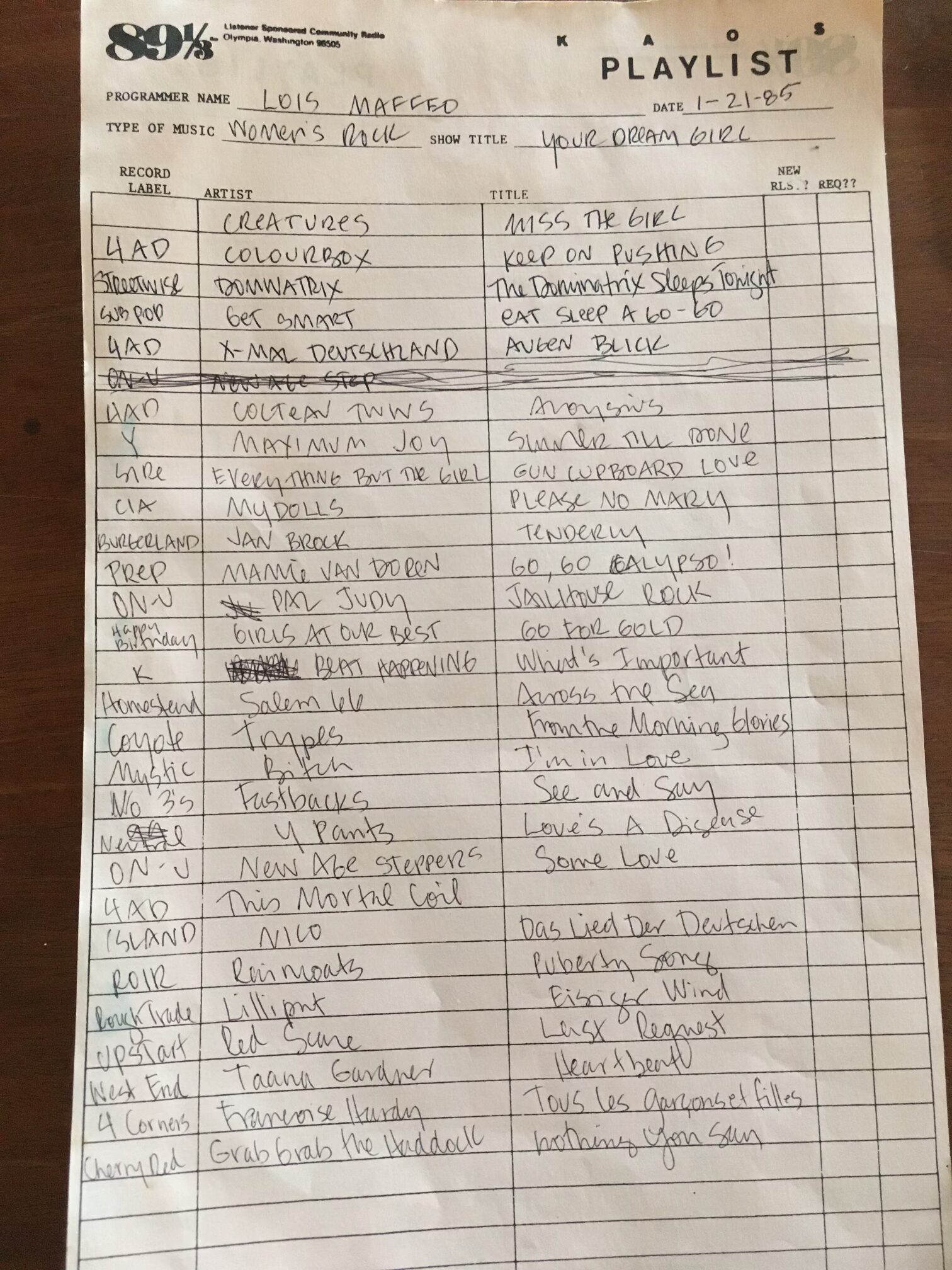

Beautiful KAOS at 89.3 FM

Unbeknownst to the band, their second life was germinating well before they’d even broken up and their first life came to a somewhat unceremonious end. It all began at KAOS, Olympia, Washington’s independent public radio station operating in partnership with the gloriously radical Evergreen State College.

Bruce Pavitt, who’s perhaps best known as a cofounder of Sub Pop Records in Seattle, developed a lifelong interest in hyperlocal music communities once he made it out to Olympia in 1979. As he saw it, the scene in Washington’s small capital city was a place shaped by the influence of The Raincoats. When Bruce left his hometown of Chicago to attend Evergreen and joined the slate of presenters at KAOS, he discovered “the most progressive music policy in America,” and what he emphasizes is “an unexplored impact.” That story actually starts with John Foster, Bruce explains.

“John was the music director at KAOS, and his feeling was that a community radio station should play music that prioritizes music made by members of the community,” Bruce says. “So he instituted a policy that stated eighty percent of what got played at KAOS had to be on an indie label. This is where I got my real education.” Bruce started his KAOS show and zine of the same name, Subterranean Pop, out of which he eventually formed Sub Pop Records to the north, “and all this flowed out of the KAOS music policy.” Bruce got a quick introduction to the Rough Trade bands, which were central at KAOS. “Rough Trade happened to be an indie DIY, of course, but what’s also crucial contextually is that they were supporting so much music made by women.” In Bruce’s KAOS show, he pulled from the station’s vast collection that included The Raincoats, Delta 5, Young Marble Giants, and others. “‘Lola’ by The Raincoats was getting a lot of airplay,” Bruce says, “and it influenced the culture of the whole community.”

As John reflects, “The one thing I can say about Olympia in the late seventies and early eighties is that it was not a bunch of snobby scenesters; folks were very nice. Everyone who participated in the scene, playing or observing, was welcome and accepted for whatever they brought. The Raincoats embodied that ethos to us.”

Bruce cites Calvin Johnson and his band Beat Happening as particularly influenced by The Raincoats, thanks to KAOS. Calvin was playing The Raincoats on his KAOS Olympia Community Radio show Boy Meets Girl. Fellow Olympia artist and musician Lois Maffeo also draws a connection between The Raincoats and Beat Happening: “It would be pure speculation to say that Beat Happening found inspiration in The Raincoats’ music, although sonically, I can see a parallel in the skronky songs of Supreme Cool Beings, whose cassette was the first release on K Records [the label Calvin would later establish in Olympia].” Referring to Calvin specifically, Lois says, “His anti-corporate philosophy and esthetic of both music-making and music-listening are central to the Northwest scene.”

Slim Moon, who’d go on to found another influential Olympia label, Kill Rock Stars, remembers Lois’s own KAOS show Your Dream Girl as a constant source of Raincoats songs. It created a dialogue among a wide and diverse range of female artists, and there was rarely a Your Dream Girl show, if there even was one, that didn’t feature at least one Raincoats track. Lois frequently drew from The Kitchen Tapes, playing “Puberty Song,” “Rainstorm,” and “No Side to Fall In.” As for the latter, Lois was completely taken in by the sound of the electric violin on that track, explaining, “‘No Side to Fall In’ just starts with that ripping scratch sound and then matches it at the end with the bare chorus of voices singing along with, what, a stick and a can? That combination of wild sound and plain sound was catnip to me! Today!” She also loved “In Love,” the first Raincoats song she ever heard when she bought a copy of Wanna Buy a Bridge? on vinyl in a Seattle record shop.

Lois regularly featured tracks from The Kitchen Tapes for a simple reason: “I was proud to own it,” she says. “I’m not a record collector/nerd/jerk in general, but I think I was bragging a little with that. I loved that tape because it was authentic-sounding. It had all the mistakes and out-of-tune moments that only happen on live recordings and I found that really invigorating.” For Lois, the cassette was also a prized possession because it “shared songs from my absolute favorite record by The Raincoats—the ‘Animal Rhapsody’ 12-inch with ‘No One’s Little Girl’ and ‘Honey Mad Woman’ on the B-side,” so she was “delighted to hear live versions of beloved tracks.” Lois loves that single so much that, she says, “It’s the only record I have two copies of. I wanted to make sure that if I wore the first one out, I’d have a backup!”

As a KAOS presenter, Lois’s show was crucial not only in cementing the significance of The Raincoats in Olympia, but illuminating a sonic lineage of which The Raincoats were a crucial part. On Your Dream Girl shows, The Raincoats played alongside artists who came long before like Eartha Kitt, contemporaries such as Kleenex/LiLiPUT [due to legal issues, the band initially called Kleenex changed its name to LiLiPUT in late 1979] and Crass, as well as more recent hip-hop and disco artists like Taana Gardner. Lois describes her playlists as “genre-busting.” That term, she says, also emerges if you listen solely to Raincoats records. “If you hear The Roches, African electric guitars, eighties NYC hip-hop, nursery rhymes, British pop,” Lois reflects, “yep, it’s there but it’s re-patterned and made into something new. Radically different from pastiche.”

Bruce is certain: “KAOS came to shape the culture of Olympia,” and “KAOS is ultimately the roots of Raincoats appreciation in Olympia and ultimately the Northwest.”

**************************************************************************

But Really, All Roads Lead to Olympia

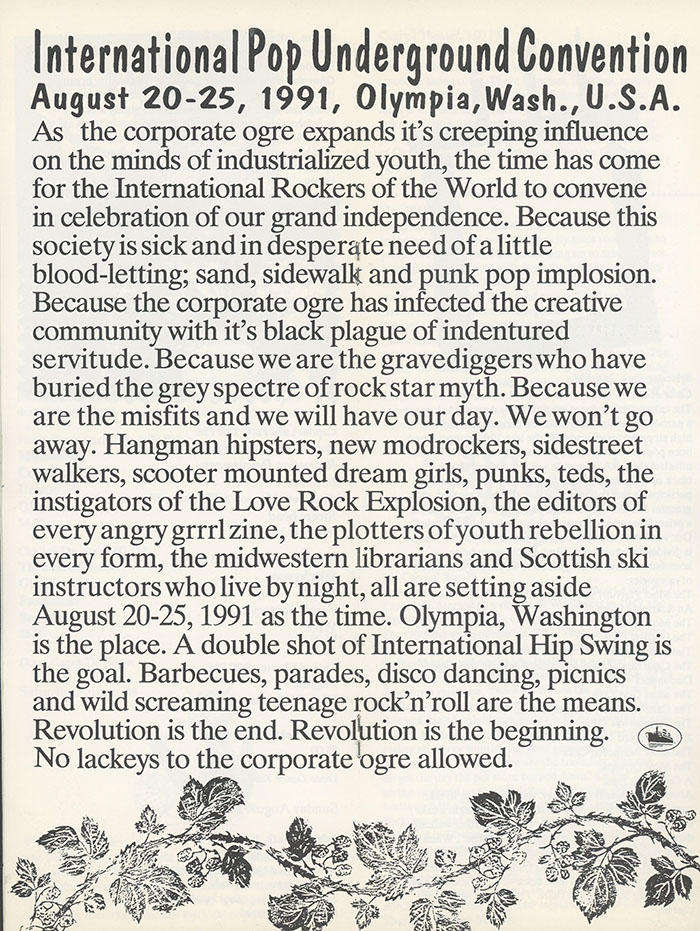

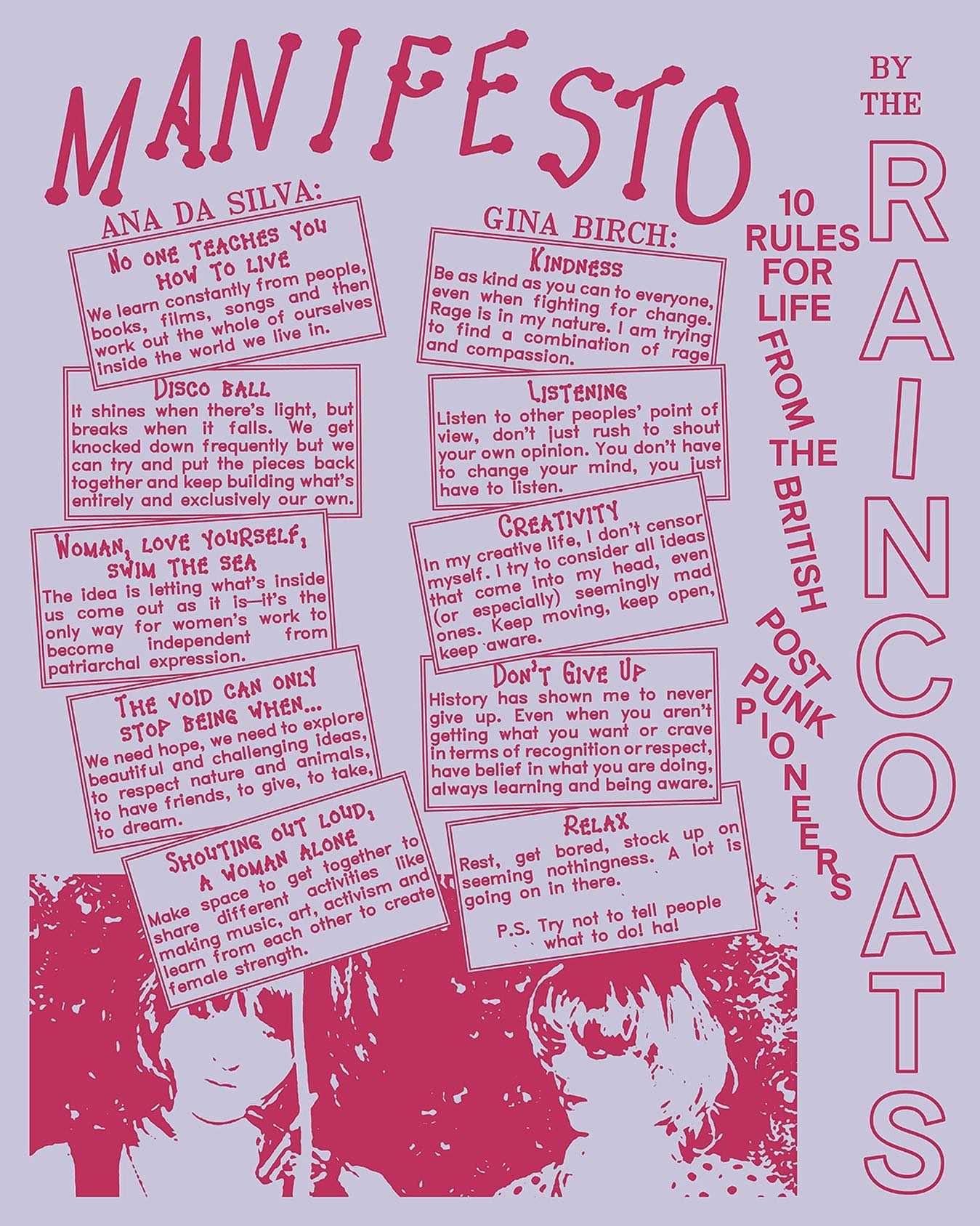

The Pacific Northwest became ground zero for the birth of The Raincoats’ second life, centered on a vibrant new generation of feminist, anarchic, queer musicians. After KAOS playlists had enough airtime to shape the cultural framework of the small Washington city, connections to The Raincoats really became apparent. Fellow West Coaster and drummer extraordinaire Patty Schemel declares, “Olympians revere The Raincoats.”

According to Lois Maffeo, the “ethos of the music and art scene” in Olympia at that point in time was akin to what The Raincoats revealed was possible: “Make do and make magic out of nothing.” Simple enough, right? But as Lois emphasizes, “The scene in Olympia was aware that simplicity wasn’t simple”—they recognized the trick of The Raincoats’ music.

The Raincoats’ songs became part of the fabric of the city and the culture it (re)produced. “The acts of making music and making art were liberating,” Lois says. “What were we liberated from? Corporate culture. Patriarchy. Religion. Military. Expectations. And many of us heard the sound of those expectations being dissected and the sound of that freedom being enacted in the music of The Raincoats. The arrow flies from ‘No One’s Little Girl’ to Riot Grrrl pretty swiftly.”

Like Lois, Jean Smith of the Vancouver band Mecca Normal was also taking cues from The Raincoats. Although Jean was based in a city a few hours north of Olympia, her two-piece band with David Lester would, like Beat Happening and so many of the Riot Grrrl artists to come, become abidingly linked to Olympia and K Records. “Listening to The Raincoats freed me from many previously held limitations,” Jean says. “That they were women made that freedom tangible. Visceral. I could hear their like-minded affinities and encouragement, yet their approaches were all very different. They seemed to be functioning based on working fully with what they had at hand, giving it everything in terms of creativity, confidence, and vulnerability.” Jean underscores that she and David are a bit older than the Riot Grrrls who emerged out of Olympia in the early nineties; Mecca Normal’s music was important, like Lois’s KAOS show, in making Riot Grrrl possible. “The Raincoats allowed me to take inspiration, to build and maintain confidence, and some years later, to inspire the cofounders of Riot Grrrl,” says Jean, “along with The Raincoats and all those other women-fronted bands that energized a social movement that, to this day, still shows signs of being ongoing as opposed to over, in the way that rock historians like to nail things down.”

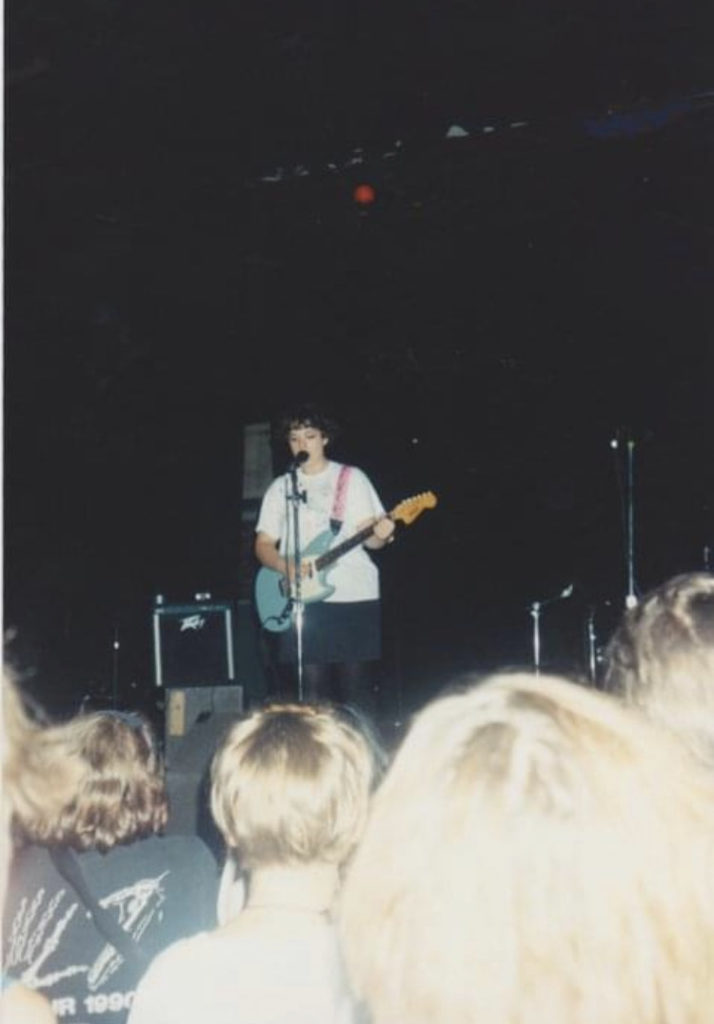

Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker of Sleater-Kinney, who were some of those original Riot Grrrls in Olympia (with the bands Excuse 17 and Heavens to Betsy), confirm Jean’s words. “I always liked how The Raincoats felt deliberately and dangerously strange,” Corin says, “and that gave license to a lot of bands in Olympia, including Sleater-Kinney, to forgo traditional instrumentation. We didn’t have a bass, and often we were playing dueling melodies. The Raincoats deconstructed all these entrenched, codified ideas about music and yet remained very appealing and clever.” Carrie agrees: “I love the artiness of The Raincoats combined with this intellectual quality. The music showed a real openness to experiment within the band that I really related to, and that avant-garde element was something that really influenced Sleater-Kinney.”

As any fan knows, the band name Sleater-Kinney originates from Sleater Kinney Road that runs through Lacey, Washington, adjacent to Olympia. “We didn’t relate to that meat-and-potatoes punk rock and were always striving for something more experimental,” Carrie says, “so The Raincoats were very influential to us in that way.” Corin adds, “I don’t know if they were trying to be ugly, with a sort of dissonance, but to us, there was something so charming about that, and that charm had teeth to it. It was a kind of cloaked weaponry that Sleater-Kinney was really into.” She continues, “With Sleater-Kinney, we wanted to say, ‘Come a little closer, and out come those teeth,’ and The Raincoats did that, too. I feel like bands in Olympia wouldn’t dare be as weird as they actually were without The Raincoats, because otherwise people are too afraid to do that stuff. But The Raincoats sounded fearless.”

***************************************************************************

In 1983, Calvin wrote one of the first US Raincoats cover stories and interviews in OP magazine, in which he asked Ana what she liked to have for breakfast (she wasn’t keen to answer). John Foster of KAOS was a cofounder of OP with Toni Holm, Dana Squires, and David Rauh. The magazine was short-lived—only twenty-six issues, one for each letter of the alphabet—and the founders wanted more Raincoats. Dana, who also served as art director for the magazine, says: “They were an influence, as they sounded like they were doing what they needed to do . . . sounded natural.” Bruce Pavitt remembers Dana’s love of The Raincoats in particular. “I very specifically remember her reproducing the Odyshape cover,” he smiled. He also describes OP as an influential magazine that did in print what KAOS did in sound, ultimately reaching a bigger audience. “KAOS DJs wrote for OP,” he explains, and, “Both KAOS and OP began getting international recognition.”

As a fan and interviewer of The Raincoats, Calvin would ultimately be the one to introduce The Raincoats to one of the artists who permanently put Olympia on the feminist map. Tobi Vail, cofounder and drummer of Bikini Kill, “first heard The Raincoats in September 1984 because Calvin put them on a mixtape for me,” she says. She was fifteen years old.

She knew Beat Happening as a local band and had gone to see a few of their shows, but she also associated Calvin with his day job: He drove a shuttle from Evergreen State College to downtown, and that’s how Tobi got to a lot of gigs. She’d also listened to Calvin’s KAOS show and was eager to know more about some of the female artists he’d been playing. Tobi spotted him one day in downtown Olympia. “I ran up to him on the street and said, ‘You just played this song on the radio, and you said the band was all girls, and they weren’t singing in English. Who was it?!’” Calvin assumed it was Shonen Knife (an all-female Japanese pop-punk band from Osaka, who’d ultimately be released in America on K Records), but Tobi insisted it wasn’t and that she needed a mixtape. It turned out the band was the female-fronted French group The Calamities, who recorded a single eponymous LP on Posh Boy Records (a Hollywood label linked to the rise of the early-eighties punk scene in Orange County). Calvin’s mixtape included The Raincoats’ “In Love.” Tobi fell in love with The Raincoats.

She started hanging out at Calvin’s apartment where she could listen to his Raincoats records, and a couple years later got her own KAOS show. “The reason I did it was because, that way, I wouldn’t have to bother other people to tape me records,” she remembers. “I could hear all the music I wanted and listen to The Raincoats [album].” KAOS was the only place in town besides Calvin’s apartment with an original copy. “I immediately started listening to that record. It got stuck in my head, it lasted, and there was more and more to discover,” Tobi says. The song “The Void” would become her anthem of sorts, shaping her musical sensibilities as she formed bands that included the Go Team (with Calvin) and, soon after, Bikini Kill. “I was obsessed,” she admits.

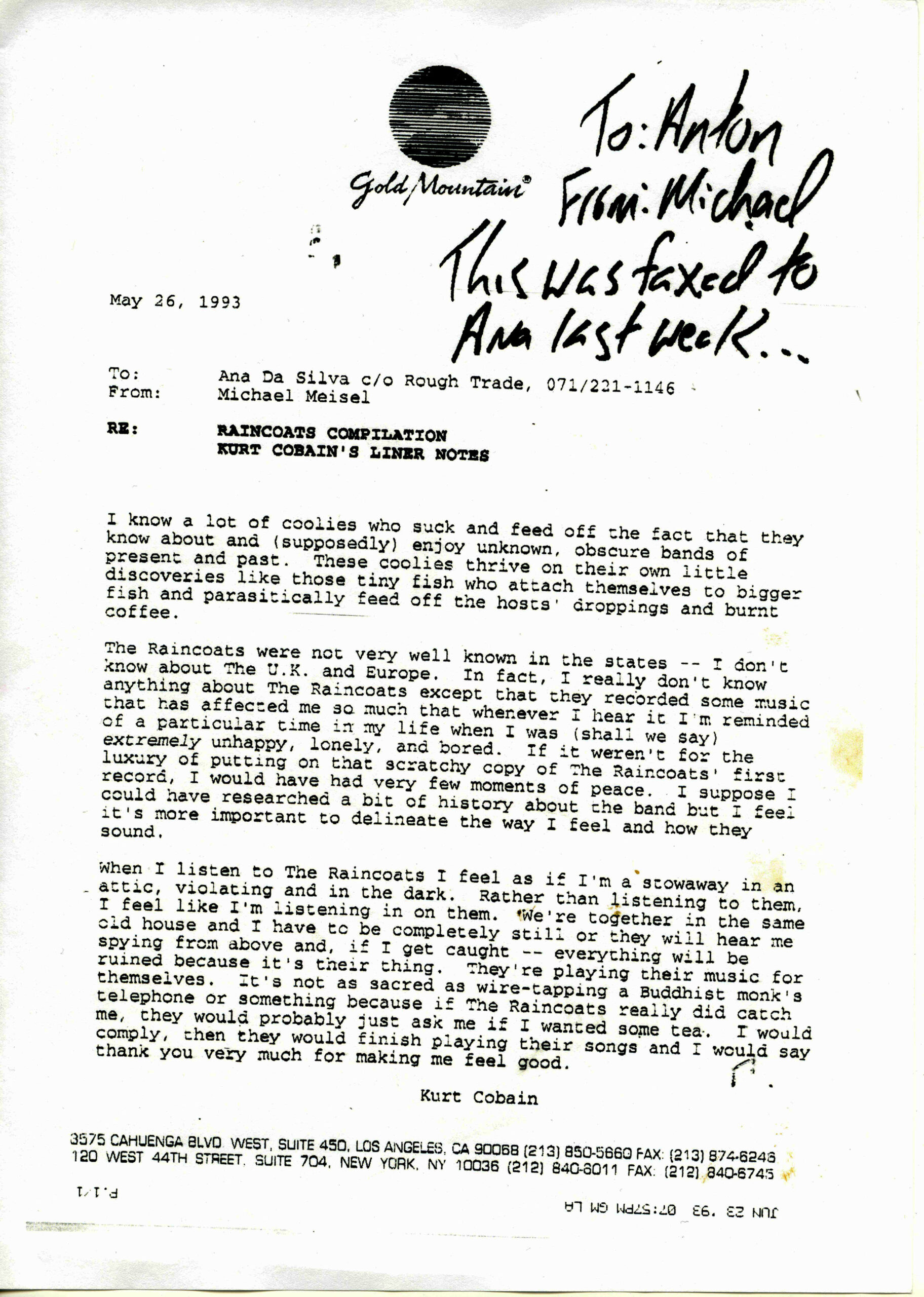

Tobi didn’t actually own the record herself for several more years—British import copies from 1979 were extremely hard to come by. “I’d never seen it in a record store here ever,” she remembers, initially assuming it was because Olympia was “pretty isolated, and the record stores here had a limited selection of punk and post-punk.” When she went on tour to San Francisco in 1987, she thought she’d find it, but nothing. “As a kid in the United States, it turned out you could only have that record if you happened to be alive and buying music when it came out in 1979.” Tobi introduced her friend Kurt Cobain, who was about to become known worldwide as the frontman of Nirvana, to The Raincoats. They’d listen to them together on the cassettes they’d recorded from Calvin’s vast collection. She eventually got her own copy when Kurt and Nirvana went over to Europe. “He brought me some Wipers records from Germany, too,” Tobi recalls.

Meanwhile, in a more roundabout way, Calvin was also the link between Kathi Wilcox of Bikini Kill and The Raincoats. Around 1984 or ’85, Kathi’s stepbrother gave her the Fairytale 7-inch EP. He was a student at Evergreen and lived across the hall from Calvin, so “he was familiar with the music scene and bought all these records,” Kathi remembers. She wasn’t even in high school yet. Eventually, her stepbrother wanted to listen to his vinyl on cassette, so he brought the goods to her and asked if she’d make cassettes of them all; the upshot was she could keep the vinyl. Fairytale was in that stack. “Suddenly I had the Raincoats!” Kathi says. “I didn’t have any frame or reference for understanding their music, but that record hit me the hardest when I got into high school and was really trying to wrap my mind around what music was.” It gave Kathi a way to completely recalibrate her thinking about songs—how they’re made and what they can do. When she eventually met Tobi, they came to one another as Raincoats fans. Kathi didn’t have the self-titled LP The Raincoats, and Tobi didn’t have the Fairytale EP, so they shared their records.

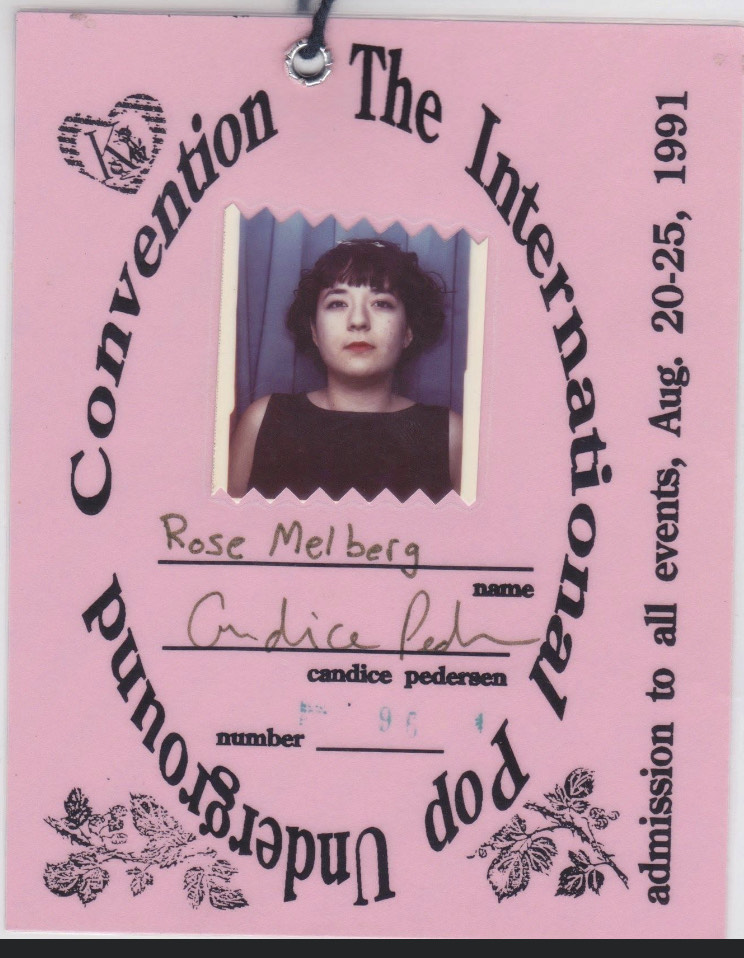

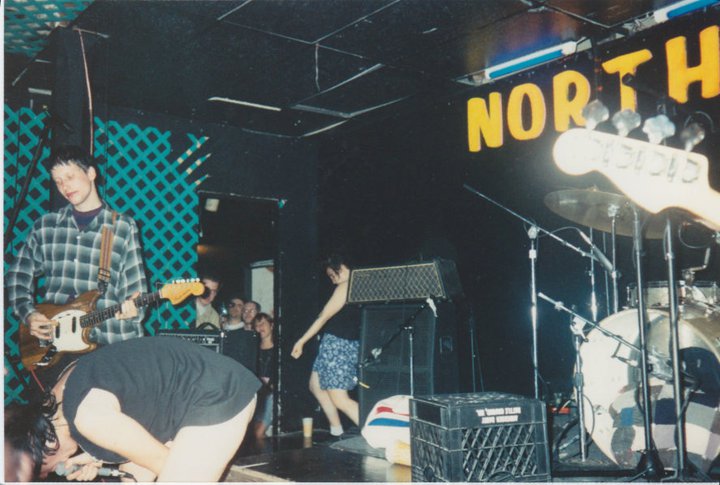

Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney confirms that the apartment complex where Calvin and Kathi’s stepbrother were living was a Raincoats hotbed. “I definitely first heard The Raincoats in the Martin Apartments in Olympia, around 1994. Everyone was looking for those records,” she says. “They were just something you were searching for. And if you had a Raincoats record, you definitely showed it off in your apartment!”

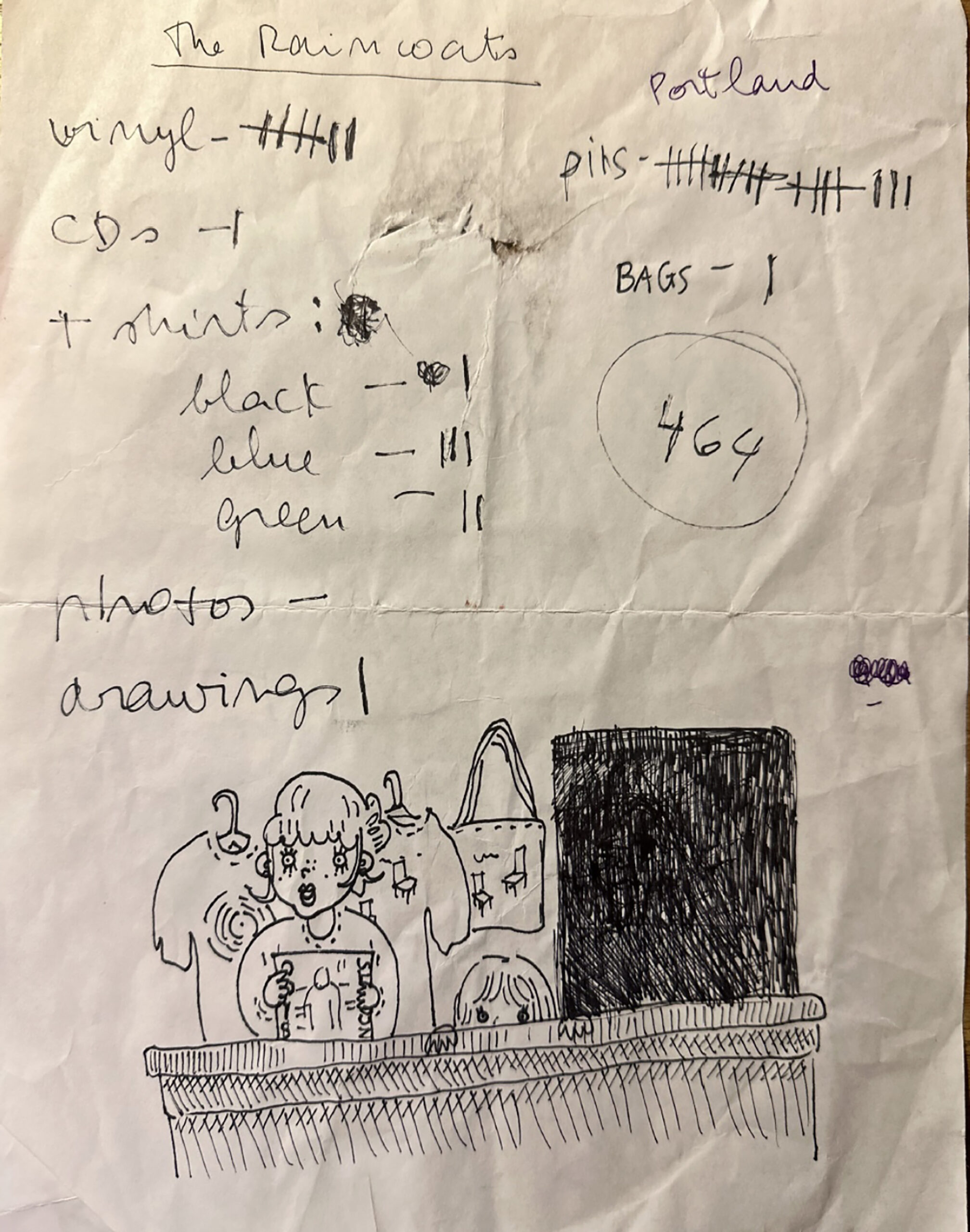

“I didn’t know then, but it seems like lots of encounters people were having with our music was through tapes, and people making tapes of tapes of tapes,” Ana says. “In Portland, Olympia, I heard from Calvin of K Records that he was doing that kind of thing, and Rob Sheffield in New York, as well.”

Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill eventually made her way to Olympia to attend Evergreen State College. It was there—thanks in large part to the ethos of a city inspired by The Raincoats—that she learned without a doubt “punk is NOT a genre,” Kathleen declares. “I was already open to the idea that punk wasn’t a genre—it’s an idea!—but listening to the bands on K Records, and listening to The Raincoats, made me know that punk doesn’t have to be this in-your-face aggressive, fuck-you music. It can be this really complicated, nuanced thing.” What punk meant, Kathleen learned from The Raincoats, “was that we could do whatever the fuck we wanted, and what felt important was making the kind of music we wanted to make.”

Excerpted from the book Shouting Out Loud by Audrey Golden. Copyright © 2025 by Audrey Golden. Reprinted with Permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Here’s Audrey in the Quietus on the Raincoats

You can read another excerpt here